On August 1, 1983, the Southampton-based Peconic Land Trust was incorporated. The nonprofit organization was founded by John v.H. Halsey, working with a small group of neighbors, including Terry Stubelek, Roy L. Wines Jr., Richard W. King and Edward Sharretts.

Forty years later, the organization has helped to preserve and protect more than 13,000 acres on Long Island, mostly on the East End, and has conserved more working farms than any other private conservation organization. It was a leading edge of a movement to preserve land — and a way of life — that gathered momentum with the Community Preservation Fund adopted by the five East End towns in 1999.

But while the CPF funds the individual towns’ preservation efforts, the Peconic Land Trust works to collect charitable donations and to connect landowners with partners who can help provide financial solutions for families while protecting the region’s agricultural heritage and natural beauty.

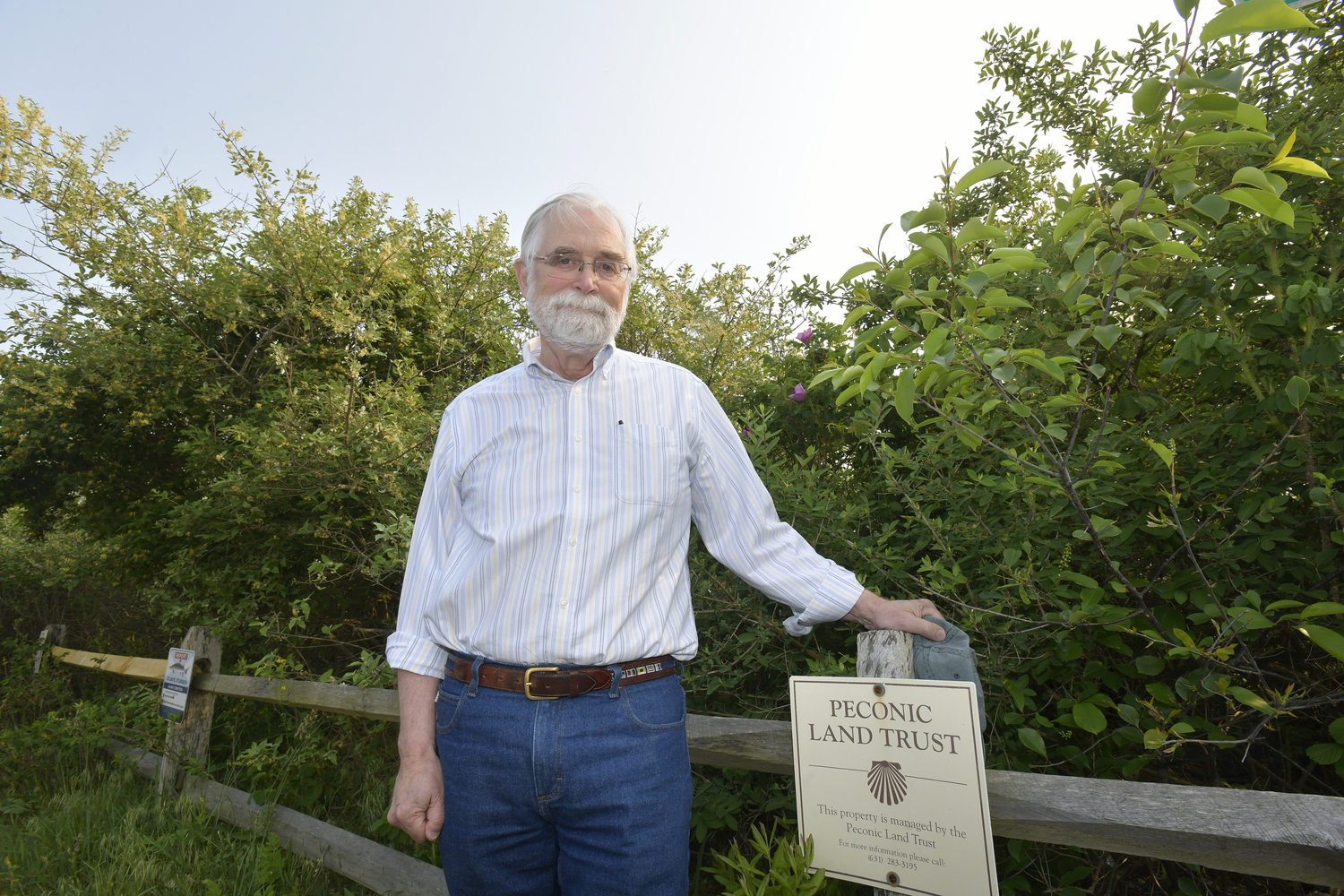

Last week, Halsey, now 71, a descendant of one of the original English families to settle Long Island, looked back on four decades of work — which coincides with four decades of marriage to his wife, Janis — and ahead to a bright future for the organization. The interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

Q: Tell me about the genesis of the Peconic Land Trust, 40 years ago — where did the idea come from? It wasn’t just your idea, right? You had the idea with some other folks in the community.

Well, I was able to entice some other people in the community. I mean, the origin, really, was tied into the fate of the farm next door — literally.

I grew up on Wickapogue Road [in Southampton Village], and, really, in my youth, from the hospital to Mecox Bay was probably a thousand acres of farmland. So the farm next door was my playground. I was in the field, I was making forts in the cover crop, the rye. I was in the barns as a kid. I was riding my bike behind the potato digger. I was probably a pest.

Fortunately, they seemed to tolerate me and all my friends who would come over, and we’d go into the fields and build forts and trails. It was really extraordinary. I lived very close to Wickapogue Pond, so that village park that exists was part of a larger block of land, so that was another area that I spent a lot of time in as a kid.

I was living on the West Coast. I spent about seven years there, and in 1980, I came back with my California girlfriend — who later became my wife, who’d never been east of Nevada, her first summer here — and there was a big “for sale” sign on the farm next door.

And I knew the family very well. I called them up and I asked them what was going on. They explained to me that their parents had died and that they had a $2.2 million federal inheritance tax, and they didn’t have the money to pay it, and they were going to sell the property in order to have the money to pay the tax.

I said, “Well, have you considered other options? Have you thought about … isn’t there a program to buy development rights?” They basically responded, “Well, government created the problem. Why would we trust government as a solution?”

I said, “Well, aren’t there organizations out here that are working to protect the area?” And they said, “Well, they don’t care about us. They just want to take our property rights away.”

They had hired an attorney from out of town because they didn’t want anyone knowing their business — it’s a small town — and, unfortunately, they got into a transaction that was contingent upon subdivision approval, and that took five years. By the time they closed on the property, I think it was a $4.1 million dollar sale. I think there was a 47 percent penalty on top of the $2.2 million [tax bill]. So a 10-generation farm basically ending up with next to nothing at the end of the day.

Q: At that time, John, was that typical? Was that a problem that a lot of farm families were facing?

Well, interestingly, as soon as I got off that phone call, I spoke to my dad, and he rattled off a few other farms … It’s really a consequence of the rapid appreciation and real estate values during the 1970s, and that’s really what caught people off guard.

Some did estate planning and got through it. Some sold their development rights and used the proceeds from that to pay their taxes. I just think that this family basically didn’t really anticipate this problem and got caught and didn’t feel comfortable looking at anything other than a sale. Not that they wanted to sell the farm, but they didn’t really see another way out.

So, for me, that really got me thinking, having grown up here and having roots here, going way back to the origins of the English settlement here, there’s always been a pull on me — if there were no Long Island, I’d still be in San Francisco. Because I love the Bay Area, I love California. But the older I got, the stronger the pull to come back.

When I saw this problem, I started talking to some of my friends — Richie King was one of them, a classmate of mine, that’s North Sea Farms, and Terry Stubelek, who was a year or so ahead of me, but a good friend — just about … “I’m really thinking that we ought to do something to try to stem the tide of what’s happening here.”

Q: When you were out in California, did you see similar organizations at work out there, or did you otherwise have a familiarity with the idea of a land trust?

Well, what I was doing right before coming here was I was working as an organization development consultant with the San Francisco Foundation. So I was working with new nonprofits, just getting started, helped start some, and also, nonprofits that were in crisis for one reason or another. So I knew a lot about the nonprofit sector.

Also, when this idea came to me, and the pull, again, that pull to come back, I began to investigate the land trust movement as a whole. In fact, when I first had the idea of wanting to return and get involved in this kind of work, there was an existing land trust, and that was the South Fork Land Foundation. I essentially reached out to them.

I had high school friends who were farmers, Richard King being one, Larry Halsey from Green Thumb. I worked on a farm when I grew up. I worked on Charlton Halsey’s farm from age 14. That was my first job, so my first working papers, and I did that for summers throughout high school. So I knew the agricultural community and had worked carrying irrigation pipes across potato fields, et cetera.

I had a connection, and I think they were feeling … folks of my generation were feeling that pressure and seeing what was happening around. Certainly my parents were aware of it. I also started talking to people like Roy Wines, who was the peer of my parents and a friend of my parents. He at the time, was the chairman of the Planning Board. I started to talk to him about land trusts, working with landowners and coming up with alternatives. He said, “Oh my gosh, John, there’s a big need for this,” because by the time someone comes to the Planning Board, it’s too late — it’s either in contract with a developer or they’ve got no other alternative but to sell the property. So he embraced the idea and was very helpful to me, opening doors to people he knew in the community.

Ted Sharretts was another one — he was a deputy town attorney. When I recognized that the best way to approach this was by creating a new organization, Ted was particularly helpful, helping me with the bylaws and the articles of corporation and so forth.

Now, I mentioned the South Fork Land Foundation. My first thought was to really help them become a more proactive organization, but they were pretty set in their ways. They were given land and they were more passive in their approach.

I said, “Well, so you guys are content just going down this path? Would you have any objection to me setting up a new organization that would complement what you do?” We would be proactive going out and meeting with landowners and really trying to help them consider alternatives to development before they’re really put in a bad position.

They said, “Go knock yourself out.”

So that’s when I began to assemble a board.

That was the origin — it was really seeing the character of this place and the farms that were literally dear to me, threatened and going away.

So, in 1983, I moved back with my former girlfriend, who was now my wife, and we moved back from California in this early summer of ’83.

Q: That’s when it got started.

Yeah, the trust was incorporated. The incorporation was completed on August 1. And I was married on May 1.

Q: Big changes in your life all at once.

Yeah.

Q: So, for people who might not be familiar with what you do, tell me about the role Peconic Land Trust plays. It’s not just, as you said, passively sort of sitting back and being an alternative for people. You’re actively out there trying to help landowners understand what their options are, with an eye toward keeping land in production, in farm production.

Well, that was truly the impetus, literally, as I mentioned the farm next door. But from our mission … the mission was clear from the beginning. The mission is to conserve Long Island’s working farms, natural lands and heritage for our communities now and in the future.

So, to me, it wasn’t just about agriculture. It was always about natural lands, woodlands, shorelines, wetlands. Because I also had a great appreciation growing up here for the water, for Peconic Bay. My grandfather used to take me up fishing in this little open red motorboat with a 7½[-horsepower] Evinrude on it, and we’d go up to Scallop Pond and fish there. To me, the whole of this place was important, and, of course, the history of this place as well.

I don’t mean just the history of my ancestors being here, but the history of the Indigenous people — and that’s always been important to me, because growing up here, going to the public school, everyone in my family had friends who were Shinnecock people. So those were strong bonds growing up.

So, to me, it was all of it, not just agriculture, but as my prior life was really focused on problem-solving and thinking about finding ways to accomplish things, it was sort of natural to approach this that way, to talk to landowners and come up with alternatives for them to consider as the inexorable pressure of development was coming down on them.

So, basically, we started out with three focuses, really. That was planning, looking at the land that people owned, understanding what their goals and objectives were. You couldn’t just go to someone and say, “Gee, you’ve got a beautiful piece of property here — will you give it to us?” Because more times than not, that was their biggest asset.

So you had to understand how they saw that land and what their expectations were of it. So with farmers, for example, they certainly weren’t interested in giving away their land, but they might be interested in selling their development rights in some instances, even donating their development rights.

So then it’s important to understand the land, and recognizing that any piece of property has … essentially, it’s an artificial box that’s a consequence of division over time. Within that box, there’s land usually that should be preserved at all costs. It could be, in the case of farmland, really the best soils. Then, there might be some marginal land, that would be nice to protect if you could do it, if you could work it in, but that next category down. Then, there’s land that could be suitable for some development, and that would be where you would put the equity lots or the lots for their children in the future.

Q: And planning all that out is what you do, right?

That’s right.

That would be sort of the first piece of the process. Second, then, is moving to acquisition of something in some way. Then, as the towns got into the purchase of development rights and land acquisitions in their own right, in the 1980s, always looking to the public sector as a potential partner, as a new fledgling organization, we didn’t have a lot of capital to make acquisitions ourselves, so we often played a facilitating role in bringing them to the table. They trusted us. They might not trust the government so much.

Sometimes people were in a position to actually donate land to us. One of our first projects was on Big Fresh Pond. There was a piece of property right on the pond that was going to be developed, and we were approached by some of the members of the community about helping to hire an attorney to block the issuance of a building permit.

So we got in touch with the owner, and his attorney was actually David Gilmartin. David was very open to exploring something other than this construction. We talked about a bargain sale, a sale less than fair market value. We struck a deal — I can’t remember the numbers. I’m going to say I think it may be appraised at … I mean, these numbers are crazy in today’s context … I think it might have been $250,000. And they agreed to sell it to us, I think, for $80,000 or $85,000.

So that kicked off a community fundraising campaign. A good friend who was no longer with us, Kurt Billing, borrowed $25,000 to contribute to that effort. His parents matched him. Someone else threw $10,000 in it. Then there were probably 50 smaller gifts. So then we acquired that property.

So that became another sort of a model that we used in the future: sometimes raising private money to supplement public money when the price tag was too big for the town to consider pursuing on its own.

So planning would move into an acquisition phase and still does. Then, after acquisition is stewardship. Essentially, it’s the management of the land that’s protected if we own it, certainly, and that can be everything from restoration to your basic ongoing, yearly management of it, but also, how does the public interface with it? So it could be a trail that we would put on the property.

Q: I’m guessing that this is a unique community where both sellers and buyers alike had a certain sensitivity — it wasn’t just about the money. It was also about, in many cases, when you could give them a reasonable option that allows them to protect the land, people on all sides were probably very open to that, because people who’ve lived here for generations, like farmers, have that connection. Has that changed over the years? Because land has become much more of a commodity now.

For sure, but then, there’s always enlightened self-interest.

I’ll give you an example: Smith Corner in Sagaponack. This was another early project. I can’t remember the exact date. I’m going to say 1989, but it might have been earlier. There was an instance where, at that point, my wife and I were living in Sagaponack. We were renting a Foster house, and we were just almost across the street from Don and Pingree Louchheim. Pingree was on the board, I think at that time, and I think Lee [Foster] was on the board. I became aware of this property that was going through an estate, and it was another branch of the Foster family, and approached them about a potential purchase.

Now, they were prepared to sell it to a builder, and they hadn’t gone to a contract or anything, but I was able to convince them to consider, if we could match that number, would they help us?

On the other side of Sagg Pond were neighbors who coveted that view. So, the bulk of the funds for that purchase came from seven donors. Six of them were pretty heavy hitters across the pond who contributed a significant chunk. One of them was Anne Aspinall, who lived in Seascape, and she also contributed to it, so she was a local. The rest of them were all second-home owners. They had, as I say, enlightened self-interest to see that property protected — and there it is today.

So every one of these projects are like a puzzle. I’ve always been a fan of puzzles. So you have to understand the pieces and then find a way to put it all together. Really finding the win-win for everyone — for the community, the neighbors, the landowner — is really a successful puzzle.

Q: So in 1999, when the Community Preservation Fund came into being, I imagine that was a complete game changer. You say it’s a puzzle — it gave you a very powerful tool to try and make the numbers work in a lot of cases, I’m guessing.

Well, remember that the towns, most of the towns, had been doing bond issues fairly regularly. So we were used to working with Southampton Town, East Hampton Town, Suffolk County. The Nature Conservancy was doing the same sort of thing.

So we were used to working with the public sector, but in working with our partners and the towns and so forth, and helping and working hard to get these referendums passed, the beauty of the Community Preservation Fund was the coalition that was built — The Nature Conservancy, the Group for the East End, Bridgehampton National Bank, a number of brokers — to create, or recreate, something that had been used in other places like Nantucket and Martha’s Vineyard. That was the beauty of it: We could spend more time doing … solving the puzzles rather than getting the voters out …

Q: For piecemeal stuff.

Yes. Yeah. So the biggest game-changing aspect of the CPF is the longevity of it. In those early years, the towns were not as equipped to do a lot of acquisitions. So, actually, the trust was hired by four out of the five towns to actually implement their program at the outset. Then, we worked our way out of jobs by helping train people within the town, help them build up that capacity to professionalize that within the towns themselves.

That created a more stable pool of public money. That was the best thing because the public money had been there. It’s just that it was more episodic.

Q: Are there a couple of projects that you look back on over the 40 years that really stand out as the successes that you would point to?

I’ll go back to one of the most significant ones in its time, and still today, was our work with Deborah Light in East Hampton, in Amagansett in particular. Deborah also was a board member, and we worked with her to come up with a plan.

It was really funny. We had gotten a small grant to do three model projects, working with a land trust from eastern Pennsylvania, the Natural Lands Trust. The land trust community, by the way, is an extraordinary resource. Everyone helps each other. So I got this grant to work with the Natural Lands Trust, and the goal was to do three model projects.

I remember explaining to Deborah: “I need one more project so I have three. Anyone have any ideas?” Silence. This was at a board meeting. I said, “Come on — you must know someone who might want to be a part of this grant!”

Finally, Deborah said, “All right, all right. I’ll be your guinea pig — but it doesn’t mean I’m going to do what you come up with.”

Well, as you heard, it’s not us dictating to the landowner, it’s: What do you want? What do you need? What’s the most significant portion of this property? So, for Deborah, she finally really understood what she was a part of, because it was really … she was driving it, and the land was driving it. What was the best farmland? So that was an incredible process.

Q: It wasn’t happening to her.

It wasn’t happening to her. It was happening with her. She was the essential element to moving it forward.

Ultimately, she started with a gift of Quail Hill. Then, beyond that, the 200 and … I guess about 210 additional acres that she gave to us during her lifetime. Originally, she was looking for some equity lots. At the end of the day, she said, “Look, I only want three equity lots, but you know what? I don’t even want them anymore. I’m going to give you this land with a moral authority to create those three lots, to provide funds to support the stewardship of this land in the area.” That was an extraordinary gift.

In so many ways, because now, today, it’s the home of Quail Hill Farm, which has so many important aspects to it. I mean, there’s just so much that that land has enabled us to do for other people.

Q: What’s great is you started with someone who was hesitant or had some reservations.

Exactly. So I would say that was a project of the 1990s, and to me, that was a real milestone project for us. What followed from Deborah was the de Cuevas family and their donations of woodland, Stony Hill Woods, John de Cuevas donating a conservation easement on 40 acres, and then his daughter and his niece donating a total of about 300 acres of Stony Hill Woods. It’s so important from the aquifer protection standpoint, a beautiful trail through our Silver Beach preserve there.

So north Amagansett just had these incredible people, the Potters and Stony Hill Farm. It’s just an amazing area that really started with Deborah, and she really became a model that others picked up on. That to me is huge.

Q: I imagine the story of the Peconic Land Trust, too, is that the successes just brought more successes, because when people saw that, they saw the impact it can have.

Yes, yes, exactly.

So a more recent project that I care deeply about and I think is so important to do more of the same, and we are doing and will do more of the same, is our work with the Shinnecock people and the protection of Sugar Loaf. To me that just … to have removed that house that was built there in 1989, 1990, on top of an area that was sacred — it is sacred — and having the opportunity, ultimately, the Town Board is going to need to approve it, when we get to the point of doing this, is giving it back. There’s a new land trust that has been formed. We’re their fiscal agent right now, the Niamuck Land Trust. To me, empowering the Shinnecock people, the Graves Protection Warrior Society, and now the Niamuck Land Trust, too, to go out and to do what we do is to me very gratifying and humbling and means a lot to me and to the organization.

It’s another piece. It’s a tricky puzzle. Sugar Loaf was really a new kind of partnership with the town, purchasing an easement and us buying the restricted land — not a novel concept in and of itself, but doing it with the Shinnecock people and for the Shinnecock people to me is important, and I look forward to more transactions of that kind.

So to me, that’s important, really to understand the history of this place, which transcends my ancestors’ arrival here by thousands of years.

Q: At 40 years, has the mission changed at all? As you look forward at this milestone, is there something different now about what the Peconic Land Trust does?

To me, the spirit that we have built in this organization is to be responsive and adaptive to emerging issues and needs among landowners, and within our communities. I expect that to continue. The fundamentals of the trust are still … I think our mission still describes what our work is, and that’s conserving working farms, natural lands and our heritage. That manifests itself in a variety of ways.

I think the use of the words “working farms” is really important, as opposed to farmland. It’s not about just the farmland, it’s about the viability of agriculture and assuring that land that has been protected — not only land that we have protected but lands that the county and the town has protected — is available and accessible to farmers, because that’s why it was protected.

That is a challenge in and of itself because there is a market for protected farmland that has resulted in an appreciation in the value of restricted farmland — because people can buy it and do nothing with it. There’s no affirmative requirement to farm it. They can buy it because they don’t want a farm next door, and they can spend $200,000 or $300,000 an acre. Most farmers, especially food production farmers, have no way of competing with that.

So I think that that’s something that emerged in the 2000s that didn’t exist early on. So we look at, “Okay, how do we address that problem? Can we come up with new tools?”

Q: It’s a new puzzle.

A new puzzle, that’s right, and to be open and inquisitive and innovative, thinking outside the box, to me, that is the cornerstone for success of any organization, quite honestly. I think that that’s been a key component to our success, is to embrace the difficult challenges.

We don’t win them all and we learn from those that we don’t win, but we win a lot. That’s very gratifying to everybody involved in it. So that that’s always been sort of the spirit of the organization. I don’t see that changing.

Of course, I’m not going to be here forever. I think for me, there’s already started in the trust, a transition in leadership. A number of our VPs have retired and people are moving up within the organization.

Q: You’ve built the infrastructure now that it can continue on, right?

I believe so, and I think that is a work in … always a work in progress. Again, with all our partners, whether it’s The Nature Conservancy, the Farm Bureau, affordable housing folks. It’s understanding the breadth of challenges facing the community and looking at how the tools that we have developed can apply in different contexts as well. So, to me, that’s the future.