When Tucker Holland glanced at the front page of his local newspaper last week, one headline immediately stood out — and came as no surprise.

“Summer Employee Housing Almost Non-Existent,” it read, the first few paragraphs of the story going on to describe what is poised to be the most difficult season to secure a place to live, with homes snatched up mere hours after they hit the market, regardless of the price.

For the predominantly second-home owner community, median sales prices are only on the rise, tipping toward $3 million, Holland explained. But despite that, the year-round population is vibrant and determined to stay put, even up against a dearth of affordable housing.

While this scenario should sound eerily familiar to East End residents, Holland does not actually live here.

He is the municipal housing director for the Town of Nantucket — an island community that is facing a nearly identical affordable housing nightmare as the Hamptons, 250 miles away.

“Unequivocally, it’s a crisis,” he said, adding, “It’s really a very similar story.”

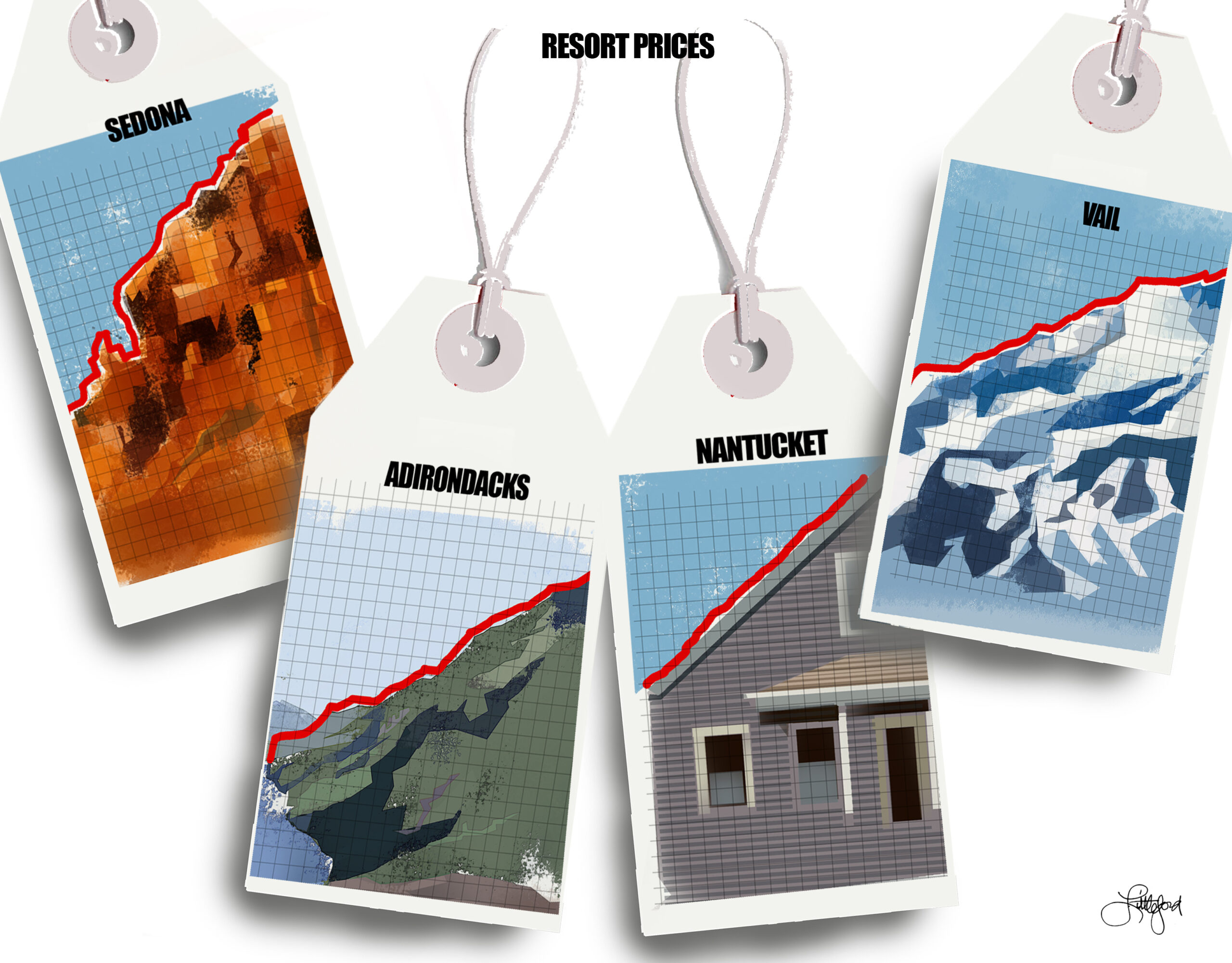

In fact, resort communities across the nation mirror the same affordable housing emergency, from the Adirondacks in upstate New York — which experienced a northbound exodus from the five boroughs during the COVID-19 pandemic — to the snow-capped ski towns in Colorado and desert oases tucked into the red rocks of the American Southwest.

“I think how we all got here is a little different,” said Shannon Boone, the housing manager for the cities of Sedona and Cottonwood in Arizona, “but every tourist town in America seems to be facing this challenge right now,”

Prior to last September, Boone’s role didn’t exist, she explained. It was born out of a 2019 housing study that highlighted the need for affordable and workforce housing initiatives in both communities — and so, they decided to join forces and combat the issue together.

“We have lots of working people who are homeless, living essentially in campers, or in their cars, in the national forest,” she said. “That’s our one benefit, that we do have a pretty decent climate year-round and lots of forest land where people can go — but no one wants people living in the forest.”

In Sedona, the median home value is rising every day, currently hovering around $850,000, Boone reported. Any house that hits the market under $300,000 is deemed affordable, she said, as are rentals under $1,300 per month — of which Sedona has just six.

“There was a time when there was market-rate housing that was affordable, and the market just isn’t anymore,” she said. “And everything that was affordable has converted to Airbnb.”

Fifteen percent of Sedona’s housing comprises short-term rentals, Boone said, “and those are only the ones that we know about.” Arizona state law prohibits the city from restricting them in any way, she explained, whether that’s charging a special fee, limiting the number, or even requiring a rental license.

“Our problem is, now, our year-round residents are being forced out by tourists,” she said, “and an increase in tourism requires more people to work in the tourism industry who don’t make any money — and no longer have any place to live.”

In towns sprinkled throughout the Adirondacks, the affordable housing crisis is rising to a fever pitch after a long period of balance between second homeowners and the year-round population, according to Patrick Murphy, cooperative housing engagement specialist for the Adirondack North Country Association.

But, like Sedona, short-term rentals have placed strain on available housing stock that, otherwise, could have gone to a single professional or family — and, like the East End, the region is seeing an aging demographic, the relocation of younger residents, and skyrocketing housing prices during the pandemic.

“I’m guessing you’re more hamstrung just because the available land is boxed in by water,” Murphy said of the East End. “Here, it’s boxed in by the Adirondack park and protected, wild forest. So the amount of available land to build new homes and put new structures on is also difficult.”

About 2,000 miles across the country, sitting at 8,100 feet above sea level, the town of Vail, Colorado, is tucked into the bottom of a valley surrounded by U.S. Forest Service wilderness area, with just two ways in — one over a 12,000-foot mountain pass and the other through a narrow river canyon, explained George Ruther, director of Vail’s housing department.

“We may as well be an island out in an ocean,” he said. “We couldn’t build our way out of this problem even if that was a possibility of doing so.”

Vail is home to 7,200 total dwelling units, Ruther reported, and about 70 percent are classified as unoccupied or vacant, according to the U.S. Census, because they are second or part-time homes. The median home value there is $2.3 million, slightly lower than Nantucket’s historic high of $2.78 million — an 85 percent increase since the town introduced a home rule petition at the Massachusetts State House in 2016 to establish a transfer fee on real estate sales over $2 million that would benefit year-round or affordable housing.

“It’s an effort that still is ongoing, although it’s gained quite a bit of steam this year, and there’s a strong push to get it over the finish line,” Holland said. “Other communities around the state have joined us, including Boston.”

In Massachusetts, Chapter 40B requires a municipality to hit a 10 percent affordable housing benchmark — Nantucket is hovering around 6 percent with 297 of a required 490 homes on the Subsidized Housing Inventory — or make “good faith progress,” which is defined by half a percent of the requirement each year with an approved housing production plan, or 1 percent without.

For those who do not meet either requisite, they are considered to be out of “safe harbor,” Holland explained, which allows developers to bypass local zoning laws and have “one-stop shopping with the ZBA,” he said, so long as their proposals allocate 25 percent of any development project to 80 percent area median income or less.

This came to a head on Nantucket when, four years ago, the island was not in safe harbor and developers Josh Posner and Jamie Feeley proposed a housing project, “Surfside Crossing,” that now calls for 156 condominium units in 18 buildings on 13.5 acres — which, as presently zoned, allows for just 21 units.

Last year, the Zoning Board of Appeals approved a scaled-back version with 40 single-family homes and 20 condo units, which the developers argued is not economically viable and brought it to the state Housing Appeals Committee.

“That kind of thing stirs up some controversy and, in fact, 800 people showed up for the ZBA meeting. That’s the amount of people who normally come to our annual town meeting. It got a lot of attention,” Holland said, adding, “It will be a shock if the Housing Appeals Committee does not effectively grant them their permit for the 156 units they were originally seeking.”

Of the 351 municipalities in Massachusetts, Holland estimates that not even 100 of them are Chapter 40B compliant. “We actually, I think, are considered to be somewhat of a leader in addressing the issue,” he said. “But still, we obviously, we’re still in a crisis. It’s not as if it’s problem solved.”

The AMI for a family of four living on Nantucket is $116,800 per year, according to Holland. The federal Department of Housing and Urban Development defines “affordable” as 80 percent of AMI, or roughly $90,000 in this case, he said — placing most homes on the market out of reach.

Across the island, desperate individuals, couples and even families with children are, anecdotally, renting rooms within multi-bedroom homes, Holland said, “and it gets worse than that.”

“I think there are families living in basements separated by a sheet,” he said. “People are doing what they need to do in order to be here, but you have people living out of their cars at times. It’s a very, very challenging situation.”

In Vail, the town’s 5,300 year-round residents live in about 1,800 free market homes, or one of over 1,000 deed-restricted residences, as part of the Vail InDEED program, explained Ruther. Through it, the town offers private property owners a monetary incentive to restrict the sale of the property in perpetuity to only those who work at least 30 hours per week, on average, at a business in Eagle County.

“We recognized that nine times out of 10, when a local resident sold their house, it was sold outside of the local market — so we were on a rapidly declining trend where, sooner or later, there wasn’t gonna be any place for locals to live in town,” Ruther said. “When that happens, a whole bunch of things occur: Schools close, business moves out of town, the community is gone. We just become a seasonal resort at that point, and we’ve always wanted to be a mountain community.”

While it wasn’t the intention, the program effectively created a secondary market for locals to buy, sell and trade with other locals — where the competition and, therefore, price range, are limited — while second homeowners strictly battle it out for property in Vail with one another, Ruther said.

“We don’t spend a lot of time talking about affordability. We have a belief that because of the resident-only occupancy deed restriction … local wages are going to begin to dictate affordability,” he said. “So if I’m a landlord or a property owner and it comes time to rent my property, yeah I can put it out there for rent for $6,000 per month, but I’m not gonna find anybody locally who meets the terms of that deed restriction who can afford $6,000 a month.”

When Ruther brought the idea in front of the town council for consideration, one of the council members asked him to talk to other communities that had a similar program in place — to which he responded that Vail would be the first.

“My comment to them was, ‘We can’t just keep doing the same things that everyone else is doing, we have to try something different and take some risks,’” he recalled. “I think as a result of taking those risks, we have substantially changed the face of housing within the town of Vail.”

Since the Vail InDEED’s inception in 2018, the town has acquired an additional 153 deed restrictions for about $10.5 million, bringing the town’s total to 1,052 properties. More than 340 year-round and seasonal residents have housing thanks to the program, as compared to the 288 residents who live within the Timber Ridge Village Apartments, which the town bought in 2003 for $20 million.

“It’s been a game changer for us. Looking back, I’m not sure where we would be today without having launched that program,” Ruther said, adding, “I just always encourage the communities I’m speaking with to stick your neck out a little bit, take some risks, try something new. The worst thing that can happen is you just go back to doing it the way you’ve always been doing it. But without trying, you’ll never really know.”

Across the country, other municipalities have adopted — or, at the very least, considered — similar programs modeled after Vail InDEED, including Sedona. “We don’t have a lot of political support for that one yet, so that’s not going forward at this point,” Boone said, “but lots of other cities are doing it and I hope we’ll get there.”

As part of a multi-pronged approach, the housing manager said that Sedona recently initiated a down payment assistance program for those who work for an employer in the city, and also aim to incentivize homeowners to provide long-term leases.

“The challenge is, right now, they’re making about $100,000 more a year on a short-term rental than they would on a one-year lease,” she said. “So we can’t incentivize them that much.”

Boone is also working to incentivize developers to include affordable units in their projects, or contribute to the city’s housing trust fund, in exchange for zoning variances. However, inclusionary zoning is illegal in seven states — Arizona is one of them — so developers in Sedona must do this willingly, she explained.

Additionally, very little land is zoned for multi-family housing, Boone said, and changes to the zoning requires public input — often spurring public outcry.

“We have some land that’s on the edge of town, but it’s not ideal to build your affordable housing layout on the edge of town,” she said. “Generally, people with lower incomes have less access to transportation and, also, it’s just not good policy in housing, in general, to put people in separate areas according to their income. We want mixed-income neighborhoods, not exclusionary neighborhoods.”

In order to encourage positive public participation in housing developments, ANCA is launching a pilot project for cooperative housing that will be “shepherded by the individuals who are the intended users of it,” Murphy said, allowing the future residents to have a say in the complete development of the parcel of land.

“We’re not saying this is the end all, be all for a solution,” he said, “but we think it could be part of a variety of tools that we could use to ensure that development projects that are looking to provide new housing, the people who are the intended users have a voice at the table for what that project will look like.”

In offering words of advice to both Nantucket and other resort communities in the midst of this crisis, Holland turned to the words of German philosopher Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe, who once said, “Boldness has genius, magic and power in it. Begin it now.”

“The longer that your community, or any community, waits or takes to address the issue, the more expensive it’s gonna be in all kinds of ways — not just dollars, but in both professional and volunteer contributions that community members make to our community,” he said. “We’re here struggling with the same issues that you all are struggling with.

“We would love to share ideas; I think reaching out to other similar communities is very constructive,” he continued, adding, “We’re not the only ones dealing with this issue and there’s a lot to learn from communities in similar situations.”