There is a moment in the four-part documentary “Vow of Silence: The Assassination of Annie Mae” when Joy Harjo, the 23rd Poet Laureate of the United States and a member of the Mvskoke Nation, states, “Every story needs to have some kind of resonance, so it can have peace.”

It’s a simple but profound statement, and in many ways gets to the heart of the motivations for filmmakers Amy Kaufman and Caroline Waterlow and director/producer Yvonne Russo, who made the film over the course of several years, in coordination with Onyx Collective.

The story of Annie Mae Aquash is not new, but the documentary is thrusting her story into the spotlight again, for a modern audience, in the streaming era, and there is a certain degree of delayed justice in the fact that many of the people telling her story this time around are not only Indigenous but are women as well.

The new documentary series, which premieres on Hulu on November 26, has ties to the Indigenous community on the East End.

Margo Thunderbird, a member of the Shinnecock Nation who lived on Shinnecock Territory and who died on October 14 at the age of 72, features prominently in the series. It tells the story of the long-unsolved murder of Aquash, Thunderbird’s friend and a fellow activist in the American Indian Movement of the 1970s.

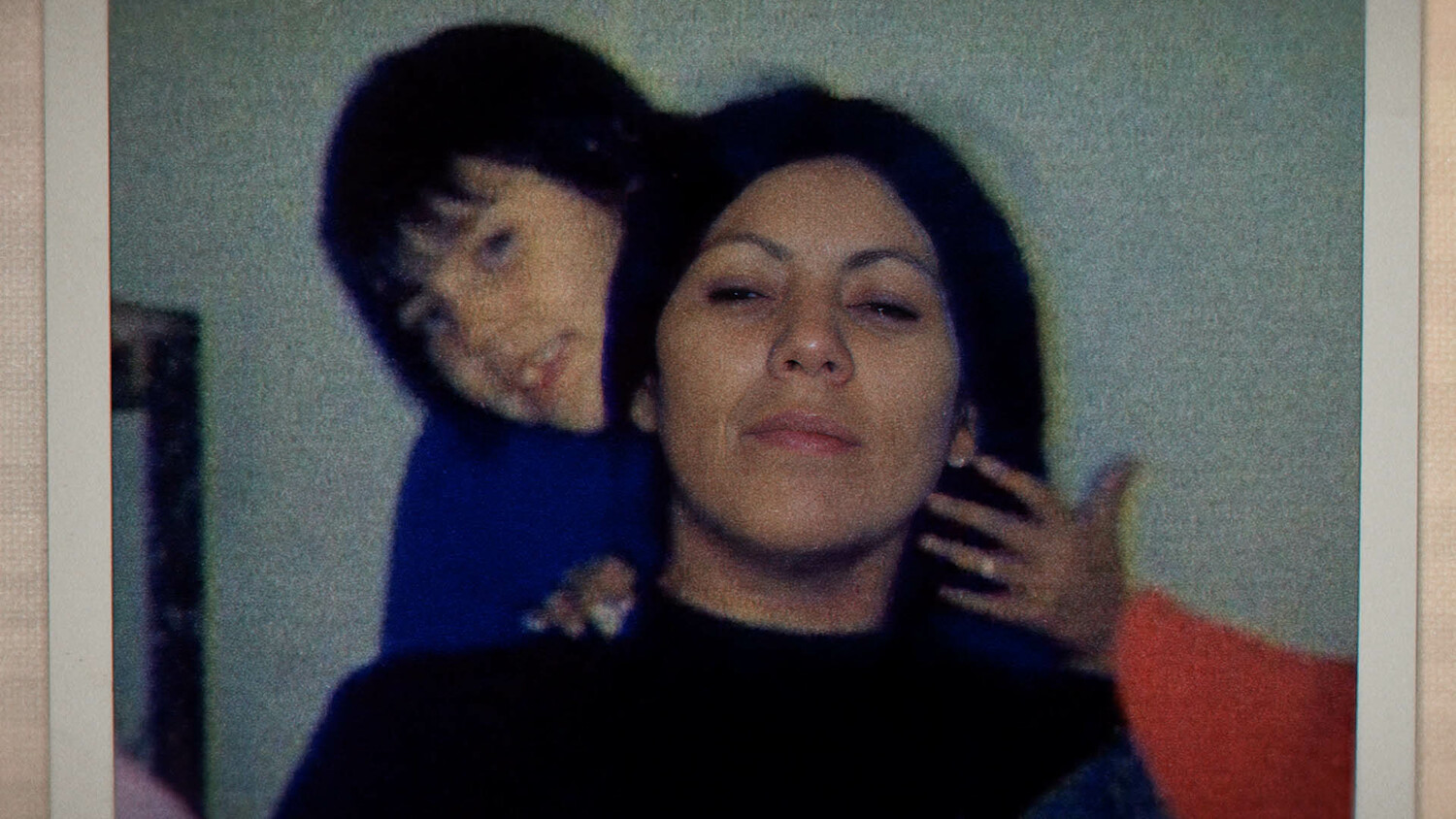

Billed as a true crime docuseries, “Vow of Silence” examines the murder of Annie Mae Aquash — a Mi'kmaq woman from Nova Scotia, Canada, a mother of two daughters, a teacher, and a revolutionary who fought for Indigenous rights in the 1970s, and whose death went unsolved for almost 30 years.

Set between the sweeping landscape of American politics in the volatile 1970s and the present-day investigation by Annie Mae’s daughter to uncover secrets from the past, the four-part series is described as “a fascinating story of murder, intrigue, love, and betrayal that contextualizes Annie Mae’s story within the larger story of the struggle of Native and First Nations women in their own communities that continues even today.”

The docuseries is executive produced by Amy Kaufman, Caroline Waterlow, Ezra Edelman and Riva Marker. Yvonne Russo serves as director and producer. It is produced by Laylow Pictures in association with Nine Stories Productions.

Kaufman — a New York City resident who spends part of her time on the East End — said she first heard the story of Annie Mae in 2017, while reading Peter Matthiessen’s 1983 book, “In the Spirit of Crazy Horse,” which chronicles the American Indian Movement of the 1970s.

That movement, founded by several Native American men, was a grassroots movement for Indigenous rights, focused not only on addressing systemic inequalities but on reclaiming Indigenous lands and rights throughout the country. Leaders of the movement frequently clashed with the federal government and FBI, leading to several tense standoffs and exchanges throughout the years.

Annie Mae became heavily involved in the movement, which moved throughout the country and had leadership from several different tribal nations, but was primarily based in South Dakota.

Despite her depth of involvement, Annie Mae was, in many ways, an outsider in the organization. She grew up in Nova Scotia, far from the Lakota tribal lands in South Dakota that were the center of the movement, and she also did not conform to the traditional gender roles that were observed in the movement, where the men were the charismatic leaders and organizers, and the women were expected to exist in the shadows in more of a support role, cooking food and doing other less visible tasks to support the movement, like answering fan mail.

Annie Mae Aquash’s killing was an unsolved mystery for three decades. The docuseries details Annie Mae’s upbringing, living off the land in Nova Scotia in what was a hard and challenging but formative childhood, and goes on to delve into how she became involved with the American Indian Movement, the chain of events that increasingly put her in danger, and the circumstances that led to her death and, decades later, finally, the discovery of what actually happened, which is revealed in the series.

Throughout the four roughly hourlong episodes, the filmmakers present a portrait of a fierce, strong-willed and also complicated woman who was deeply passionate about fighting for the rights of her people, and ultimately sacrificed her life for the cause, in more ways than one.

Having the involvement and blessing of women like Harjo and Thunderbird, as well as Denise Pictou Maloney, one of Annie Mae’s two daughters, on the film was essential, the filmmakers said, and they spoke in particular about why they wanted to bring Thunderbird on board.

“It’s really important for us to have the voices of the women speak,” Russo said, pointing out that it was particularly crucial because so much of the American Indian Movement leadership was male. “We wanted to have people who were from the movement that were Annie Mae’s friends and were still alive.”

Russo and Kaufman made several visits to the Shinnecock Nation to speak with Thunderbird for the film, and had many conversations with her before Thunderbird agreed to come on board.

“I reached out to Margo, and the first time I met her, she was very skeptical, which was understandable,” Kaufman said. “She wanted to know who I was, why I wanted to tell this story, why I should even be involved. She said to me, ‘You have a lot to learn,’ and I knew she was right in that moment.

“I was able to learn a lot,” Kaufman continued. “And I hope people learn a lot by watching this film.”

Kaufman said that Thunderbird made it clear that she believed an Indigenous woman was the one who needed to be telling the story, and Kaufman and Waterlow agreed. That is why they brought on Russo, an accomplished filmmaker who grew up on the same reservation in South Dakota that was the heart of the American Indian Movement.

She said that having the opportunity to direct and produce the film was a “full circle” moment.

“I was a kid on the reservation after Annie Mae’s murder,” Russo said. “I was 9 years old and living in Rosebud, South Dakota. Her story has been with us for decades.”

Russo spoke about why it was so meaningful for her to produce and direct the film, aside from her personal ties to the story.

“Annie Mae is an ancestor,” she said. “She’s our ancestor now, and this is an ancestor story. It’s an important story, because it’s one that has been kept silent for decades.”

Lifting that veil of silence with the film required not only the involvement of the right people, but their blessing as well. Kaufman, Waterlow and Russo all spent time with Pictou Maloney, traveling to meet with her in Nova Scotia, spending many hours learning about her mother and how and why she dedicated her life to the cause.

“I really wanted to understand who she was as a person,” Russo said of the importance of spending time with Pictou Maloney in order to get to know her mother’s story. “I wanted the blessing of her family. And I wanted to see where Annie Mae grew up, to be one with the land she was from. That’s what she was fighting for.”

Having Thunderbird’s direct involvement and support was vital as well, the filmmakers said, not only because she was friends with Annie Mae but also because she lived through that time and was active in the movement at that time.

“It was important to have a first-person accounting in the day of the life of being a movement member,” Russo said of Thunderbird. “Margo was such an amazing, dynamic woman, who I feel lived multiple lives. To have her blessing on it was really important. She knew [the story] had to be told from the people, not with a narrator or an expert. That’s the only way the story could unfold.”

That is precisely how the docuseries does unfold, and is the primary reason it is so compelling. The filmmakers had access to a rich archive of interviews and footage from that time, and also received an anonymous donation of hours of cassette recordings of interviews from that time, related to the crime.

Waterlow, a seasoned documentarian who is best known for the film “O.J.: Made in America,” explained her motivation for coming on board and being part of the filmmaking team for “Vow of Silence.”

“I love all things historical, where you can dig in and look at the context of things, particularly when it comes to female leadership and political movements,” she said. “It ticked every box for me in terms of the kind of storytelling I’m interested in being a part of.”

Annie Mae certainly was a riveting figure when it came not only to the mystery that surrounded her death for so many years, but for the unique way she defied conventions within the movement, in ways that undoubtedly put her at risk.

“Annie Mae was a warrior,” Russo said. “She studied karate, she handled weapons — she had her own gun. She was tough, even though she was only 5 feet, 2 inches. She grew up by the fire and lived outdoors. She was with the men a lot.

“She was an outsider coming into a community that was tight,” Russo continued. “As Lakota people, they were a very tight community. Annie Mae was a hard worker, but an outsider coming in, and there was probably a bit of naivete in terms of asserting herself so quickly amongst the leaders, where there were probably some people questioning who she was.”

“Annie Mae was a woman who wasn’t going to just talk about changing,” Kaufman said. “She saw a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to change the world for her kids and decided to stand up and fight. I think we all have a lot to learn from her.”

In the film, Thunderbird speaks about those characteristics in Annie Mae, which she greatly admired, and it is clear that Annie Mae, who was a few years older than Thunderbird, served as a role model for her.

Thunderbird maintained that same kind of assertive, fighting spirit throughout her whole life, even after her years involved in the American Indian Movement, leading the charge in fighting for Shinnecock rights and causes back at home, often on the front lines, even as she grew older and faced health challenges.

Thunderbird died before the docuseries premiere, but the filmmakers said they were happy to report that she was able to view it before her death.

“We shared the final series with Margo before she left us,” Kaufman said.

“One of the things we’ve talked about is that it’s known that women are often erased from history or they’re the workers behind the scenes. One of my greatest satisfactions was being able to watch Margo watch this series and see her pleasure in the story being told and knowing it will get out there in a big way.

“She said she hopes young people in her community can see the film and know these stories,” Kaufman added. “I hope this is a movie for them, and I know it’s also a movie for everybody. There’s so much we can learn from her story.”