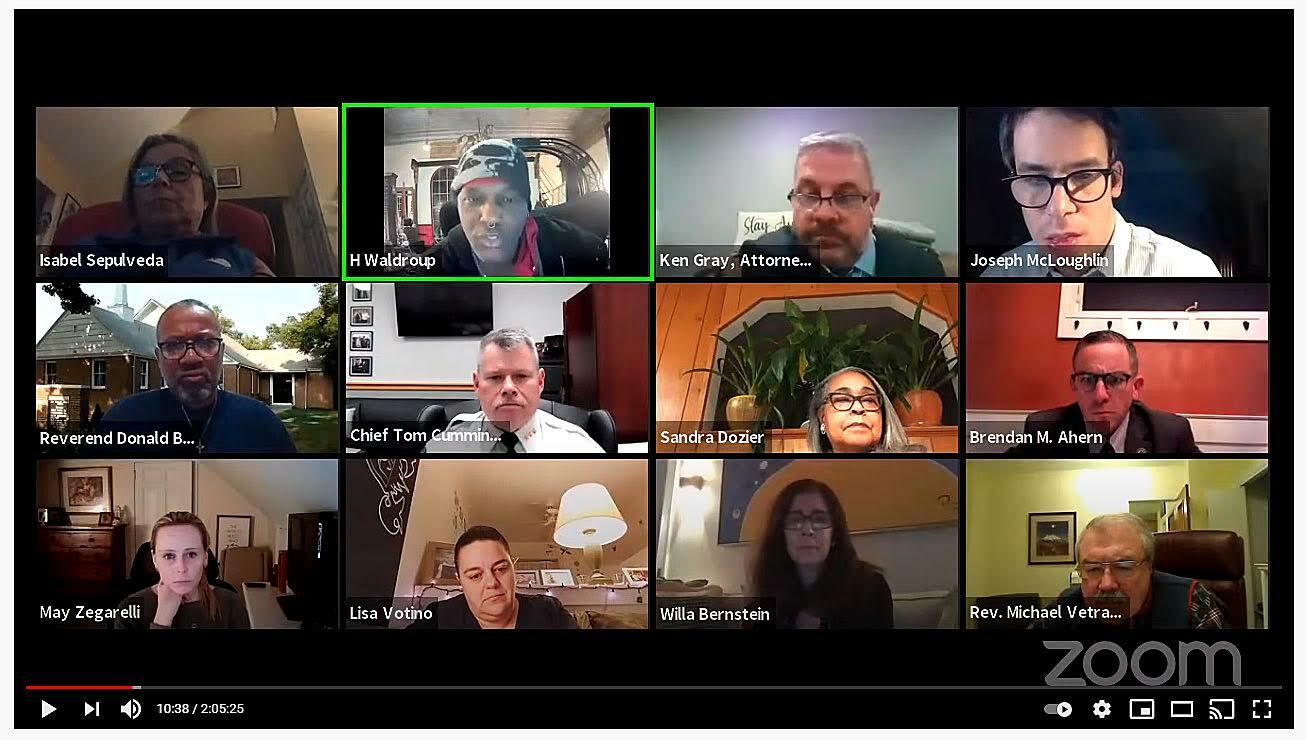

As the trial of Derek Chauvin, the former police officer charged in the death of George Floyd commences in Minnesota this week, the work that has begun across New York State to address bias in police departments edges toward its end. Under orders from Governor Andrew Cuomo, most local villages and towns have concluded compiling their mandated police reform and reimagining plans.

While the villages of Quogue and Westhampton Beach held public hearings on plans that drew little comment this week, Southampton Village’s stakeholders, convened later in the game than most, continue to hold meetings.

And, for at least some of the stakeholder participants, the group’s discussions merely expose how much more work needs to be done, particularly when it comes to race.

On Thursday, March 4, committee member Hulbert Waldroup criticized Village Attorney Kenneth Gray, describing his attitude toward Mr. Waldroup’s experience of “Driving While Black” in Southampton Village as “very cavalier.”

The previous night, Mr. Waldroup told fellow members of the stakeholder group about a moment when he was pulled over in the village and interrogated about where he was going, why he was in the area, how he ran his business and developed his client base. All the questions were asked before the officer finally mentioned that Mr. Waldroup’s inspection sticker had expired.

Mr. Gray, endeavoring to point out that expired stickers are easily seen by police, said that he, too, was pulled over once for an expired inspection sticker. Mr. Waldroup persisted, underscoring the invasive questions “Mr. Friendly” was asking, in an effort to show the differences in the two experiences.

“You never have been driving while Black,” another stakeholder, the Reverend Donald Butler, said to the attorney. “There shouldn’t have been a rebuttal.”

Mr. Gray, who is white, doesn’t know how a Black man feels when he’s pulled over by police, Rev. Butler said.

Discussion moved quickly to another topic. Committee member May Zegarelli, a legislative aide in Southampton Town, changed the subject, describing her experience observing the efforts of the village police in assisting a homeless person.

While issues of police and race were the impetus for the governor’s executive order requiring reform and the convening of citizen committees, “The homeless lady got more airtime,” Mr. Waldroup said the next day.

After he told his story to the group, “There was no explanation. There was no resolution, there was no ‘That won’t happen again,’” Mr. Waldroup said. Discussion just moved on to another subject.

Asked why he didn’t offer a response to Mr. Waldroup’s story, Village Police Chief Thomas Cummings said this week, “He didn’t file a complaint.”

Throughout the March 3 meeting, as well as another discussion on March 9, improvements to the complaint process were considered, with committee members emphasizing that some people, particularly minorities, are uncomfortable taking complaints directly to the police.

“I don’t want to see Mr. Friendly again in this life or next, and I don’t want to see Mr. Friendly’s friend to complain about Mr. Friendly,” Mr. Waldroup asserted, explaining why he hadn’t filed a formal complaint after the upsetting traffic stop.

Stakeholder Lisa Votino echoed the assertion. “Who’s friends with who? … That’s what I hear, and that’s why you only get six complaints in a year,” she said.

The village stakeholder group meeting was described as a “listening session,” by Mr. Gray. However, there were no members of the general public in attendance.

Michael Horstman, head of the village PBA, suggested people didn’t show up to speak because everyone is satisfied with the department.

“I think it’s a sign people are thinking we’re actually doing a good job,” he said.

“I think they don’t know about it,” Isabel Sepulveda interjected. Other members had questioned how well the meetings were publicized. Mr. Gray, who stepped in after his predecessor, Brian Egan, resigned in January, said he was unsure of how word of the meetings was disseminated.

Speaking to Mr. Horstman’s statement, as well as the department touting few complaints each year, Ms. Votino said, “We need to stop pretending there’s no problem whatsoever.”

People are uncomfortable with the police, Rev. Butler, a retired police officer, pointed out. Like others in the group, he supports the village having someone who can act as a go between when there’s a complaint — an early draft of the group’s report suggests the village administrator.

Mr. Horstman balked at the suggestion of a civilian review board to serve as a buffer for those with complaints. Stakeholder Willa Bernstein, an attorney with a background in criminal law, suggested a group of people who are not political, not an arm of the government, be selected to address complaints. Mr. Horstman pointed out that when there’s a complaint about an attorney, the Bar Association addresses it, not a group of civilians.

“It’s not rocket science,” Mr. Waldroup countered at the March 9 meeting. Members of any review group just need to know right from wrong, he said.

People are generally uncomfortable speaking about race, Ms. Bernstein said Saturday, reflecting on the group’s reluctance to dig deeper into Mr. Waldroup’s “driving while Black” profiling complaint.

“We have to honor the experience of minorities who feel threatened with suspicion and hostility in a routine traffic stop,” she said. The whole point of the governor’s mandate, she said, is “to listen to those stories and take them seriously.”

She felt one of the important things in Mr. Waldroup’s story was the fear of repercussions and how that has a chilling effect on complaints. “There’s a feeling of futility,” she acknowledged.

Still, Ms. Bernstein believes there’s a consensus in the community that change needs to occur, that the system needs to transform so people feel more secure.

Looking at the process of compiling a reform plan as a whole, Rev. Butler said Friday, “They threw us in the pan too late.” With an April 1 deadline for submission looming, Rev. Butler felt there should have been more meetings earlier in the process. Governor Cuomo called for each municipality to craft its plan, with input from stakeholders, last summer. Southampton Village stakeholders didn’t begin to meet until January. Having met on March 3, committee members planned another two meetings March 9 and March 10 before submitting the plan to the Village Board for review and adoption.

The governor’s order doesn’t require the board to hold a public hearing on the plan. Given the laws surrounding notice of public hearings, there wouldn’t be time to schedule the hearing before the last meeting of the month.

While it wasn’t required, the villages of Westhampton Beach and Quogue both held public hearings on their plans, which were posted on their corresponding websites last month.

In Westhampton Beach, Village Mayor Maria Moore presented the draft plan at a public hearing on March 4. The Reverend Jack King, pastor of the Beach United Methodist Church, complemented village officials and volunteer stakeholder participants for the “beautiful job” they did pulling the report together. Police Chief Steven McManus said he looks forward to moving ahead with suggestions in the report. No other member of the public spoke, and officials expect to adopt the plan at its next meeting.

In Quogue Village, input was similarly sparse. Introducing the plan, Mayor Peter Sartorius said he was pleased to have a “top rate group of people” serving in his police department, led by Chief Christopher Isola and Lieutenant Dan Hartman. The chief said that he and his department embraced the process of crafting the required plan “because we’re proud of what we do.” He emphasized that when it comes to the national landscape, “we are listening and paying attention.”