By Lee Foster

The phragmites that appear to be choking the small, shallow secondary body of water just east of Sagg Pond are an indication that, over time, what is now barely covered by water will become a bog.

It is on the left as one passes by on the way to the beach. Depending on the encroachments of the residential homes along Sand Dune Court, and the advance of warmer, drier years, this mud flat will become a thumbprint of a previous body of water.

Perhaps beneath the evolution of this marine environment there is a series of tracks that are evidence of a bulldozer, which entered the pond and then, in reverse, backed out.

This might become a fossilized record of an event that took place in 1958 — unless it’s completely consumed by the sea, which actually seems more likely.

There was no question in my mind as to how the bulldozer got there. For years, however, I’ve been curious as to the actual circumstances and how they unfolded.

Recently, deciding to find out more, I attempted to contact anyone still alive who might have remembered what I defined as the “incident.”

There was no comment in the archives of the Bridgehampton News or The East Hampton Star. I was told that if there had been an arrest, there were no records that could be retrieved in the files of the local police, not even an entry about a group of 20-year-olds who needed discipline.

Many of the “farm boys” I knew at the time have gone. That would have included Tom Conklin, Dave Osborne, Bud Topping and Howell Topping. One person I knew to be involved was Cliff Foster — whom I married in 1963 — and he’s gone, too, but there is the thread.

•

In 1958, I was living with my family in a beach shack, a 20-foot-by-40-foot structure set up on pilings, placed on the dunes and located to the left of the parking lot presently at Sagg Main Beach.

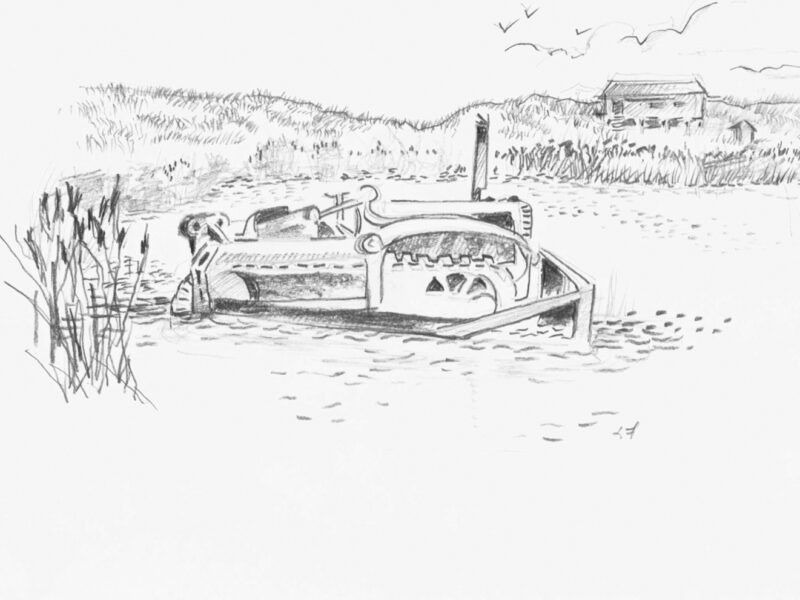

The shack had been built in 1911 and had not changed much. From the back porch, overlooking the few feet to the outdoor privy and another small cottage closer to the road, I woke up on an August morning and saw an International TD-14 bulldozer, enhanced by the bright summer sun, sitting in the middle of that small pond. The water came halfway up the cleats.

I remember thinking, hopefully, that perhaps it would sink.

I was 15. Although living on the beach, I was often kicking around at the Toppings’, where there were cows, turkeys and Muscovy ducks, and Warren and Helen and their son, Bud.

Up the road, where Cliff lived, there was always a job. Something was always being constructed. One summer, I scraped and sanded and applied varnish onto the mast and gunnels of a sailboat. And then we sailed on Sagg Pond. Cliff was building a potato harvester.

On that day, when Cliff and his closest friend, Howell Topping (who lived in Wainscott), were asked to appear before a magistrate in Bridgehampton, I was hanging out at the farm, wondering if I’d ever see Cliff again before he went to jail.

I remember standing, facing the wall in the dusky shop at the farm, where nothing was going on. It was very evident that the boss was being detained elsewhere. I rubbed my fingers back and forth along the edges of an old phone, which hung on the wall there. I felt, then, that I had caused the awful thing that now was interrupting things — the normal, everyday things.

I have that phone in my kitchen presently. It sits on a chair next to the back door. About a month ago, I retrieved it from the shop, because eying it, dust-covered and pushed into a corner, it coaxed me to try to clarify and better understand this story, and I brought it home. Artifacts can do that.

That phone, on which I centered myself with worry that afternoon, had been amended to only communicate between the Foster house and the shop, a method of calling the men for meals. It has a crank on the side, two bells and an earpiece attached with a wire — a relic of the time in Sagaponack when one rang up the operator and asked by name to speak with a neighbor. “Just a minute, please,” the operator would say as she inserted the plug into the switchboard that was situated in a building on Hull Lane in Bridgehampton.

That phone, then, was next to the real one, the dial-up that was used to contact the outside world. I wanted the real one to ring to tell me that all was well.

Cliff’s mother, feeling confused by this event, was in a small torment that even I could see as she tended to some laundry hung out earlier to dry. Anne was thin and affected by rheumatism. She limped, favoring a sore hip, but had a steely resolve.

She said quietly to herself that there was a misunderstanding, and that her son couldn’t be — could never be — arrested. I never saw anything of Cliff’s father that day, and don’t know that he had any interest or was even involved in any way.

All that I could recall was that by the end of the day, Cliff had returned and not much more was ever said about the details.

•

But my memory of that sweet August evening, now 75 years ago, is still very clear.

When the farm boys came to the beach for a swim, as they did about every afternoon, there had been some discussion as to why that bulldozer was parked on that farm field, and how it really had no business being there. Bud and his father, Warren, had leased that field for years, growing potatoes, cabbage and grain.

After dark, aware of activity nearby, I quietly exited the shack, crouched low, and crept through the slippery, wet dune grass. I made my way toward the voices I heard. I felt the cool streaks of dew on my legs; the sand was still warm beneath the surface damp.

I knew that I had added my two cents earlier, saying things like, “Yeah, go, get it out of there! No need for it to be there!” or something like a teenager, eager to demonstrate some power, might say to men who honestly could do something about it.

I returned to the shack on the dune, without anyone knowing that I had hidden nearby, but I heard the engine start and felt exhilarated that someone could make a statement beyond words of protest.

Of course, after marrying Cliff, that incident had been described — it was the kind of story told at the dinner table or reveled about among friends knowing past times. Elements, however, made the story incomplete.

Why hadn’t there been a court date? Whose bulldozer? Who actually was there? I even asked around about a particular priest who was named three times, Father Joe Rapkowski. He was known to be the type of person who, then at The Queen of the Most Holy Rosary Church in Bridgehampton, would advocate for a couple of rash young men and maybe put up bail.

Cliff had said that Howell Topping put the bulldozer in gear.

•

One of the last people I spoke to was Ed Vinski, a professor of education, living in Bridgehampton. He had no information but did have a bit of background material in light of his father’s father, Frank Vinski. Ed dug a little deeper through his own siblings and cousins and then called me, suggesting I speak with Harry Helstowski.

Harry Helstowski greeted me at the door as I met him recently: 90 years old and living just north of me, surrounded by woods. He lives in the house he built in 1977. He and his wife, Nancy Jessup, settled there and raised their family.

Harry is a broad man, basically unbowed, and has the meaty hand, which he offered, that is still full of work. I introduced myself and quickly came to the question I most wanted to ask: “About that incident on Sagg Pond in 1958 …”

He just nodded his head and quietly said, “Ray.”

He went on, “J.J. Haggerty ran a contracting business in Westhampton and was hired to push a road in — I think it’s Sand Dune Court — and I was working with my brother, Raymond, for Frank Vinski and Sons, the local paving company. We were doing the same kind of thing.

“Frank was our stepfather, having married our mother, Josephine Helstowski, after she lost her husband, Harry. I’m named after him.

“Ray got the bulldozer started, and Cliff ran it into the pond. They couldn’t get the gas pony engine to engage but figured it would at least run for a while. It quit in the middle. If they’d gotten it switched to diesel, it would have crossed the pond, gone over the dune banks and into the Atlantic Ocean.

“A lot would have been different then. As it was, the boys probably squealed on each other, and so were invited to ‘come along.’ It was up to Bridgehampton, where Judge Hallock had an office. He gave them a talking to and told them to stay out of trouble and let them go.

“It was just those three: Howell, Cliff and Ray. I don’t recall, but Frank did have a temper, and even though he quickly cooled off, I think Ray caught a bit of hell for being involved.”

Someone, of course, had to take a can of gas to start the dozer and then return it to shore. But this I didn’t need to know.

For years, when repeating some of this story, I had attempted to believe that the passion of farm boys had pitched them into the genre of environmental terrorists. The bulldozer symbolized the ominous destruction to follow. I’m still of that bent, knowing how much of that fear has unfolded exactly so.

But the other aspect related to human behavior is rank competition. That and young men seeing if they could get something to run.

We continue on, elevated or buried by the force fields of these things. Known to history by the fossils and the artifacts we leave behind.

True story.

Lee Foster is a resident of Sagaponack.

More Posts from Viewpoint

More Posts from Viewpoint