Even though his office was above the floors where United Airlines Flight 175 struck Two World Trade Center, William Wik somehow, apparently, made it out of the building alive.

But then, it seems, he went back in.

Mr. Wik’s sister, Kathleen Wik of Sag Harbor, was at work at the Parrish Art Museum in Southampton Village when she heard about the first plane striking One World Trade Center.

She tried frantically to get in touch with her younger brother, who had started a new job at the insurance giant Aon Corporation, which had offices spread over 10 floors of Two World Trade Center, just two months earlier.

“I tried to get in touch with him, but I couldn’t, so I immediately jumped in the car and headed for the city,” Ms. Wik recalled recently. “I was in the car when the second tower got hit. I was one of the last cars that got over the Throgs Neck Bridge.”

Like so many families on that day, the Wiks then began a gut-wrenching search for their missing loved one.

They visited hospital after hospital. They waited with thousands of others at the Manhattan Armory, where emergency workers were compiling information about those missing, and families began posting photos, pleading for information, that ultimately became the most lasting illustration of that day — and is now an exhibit at the National September 11 Memorial & Museum.

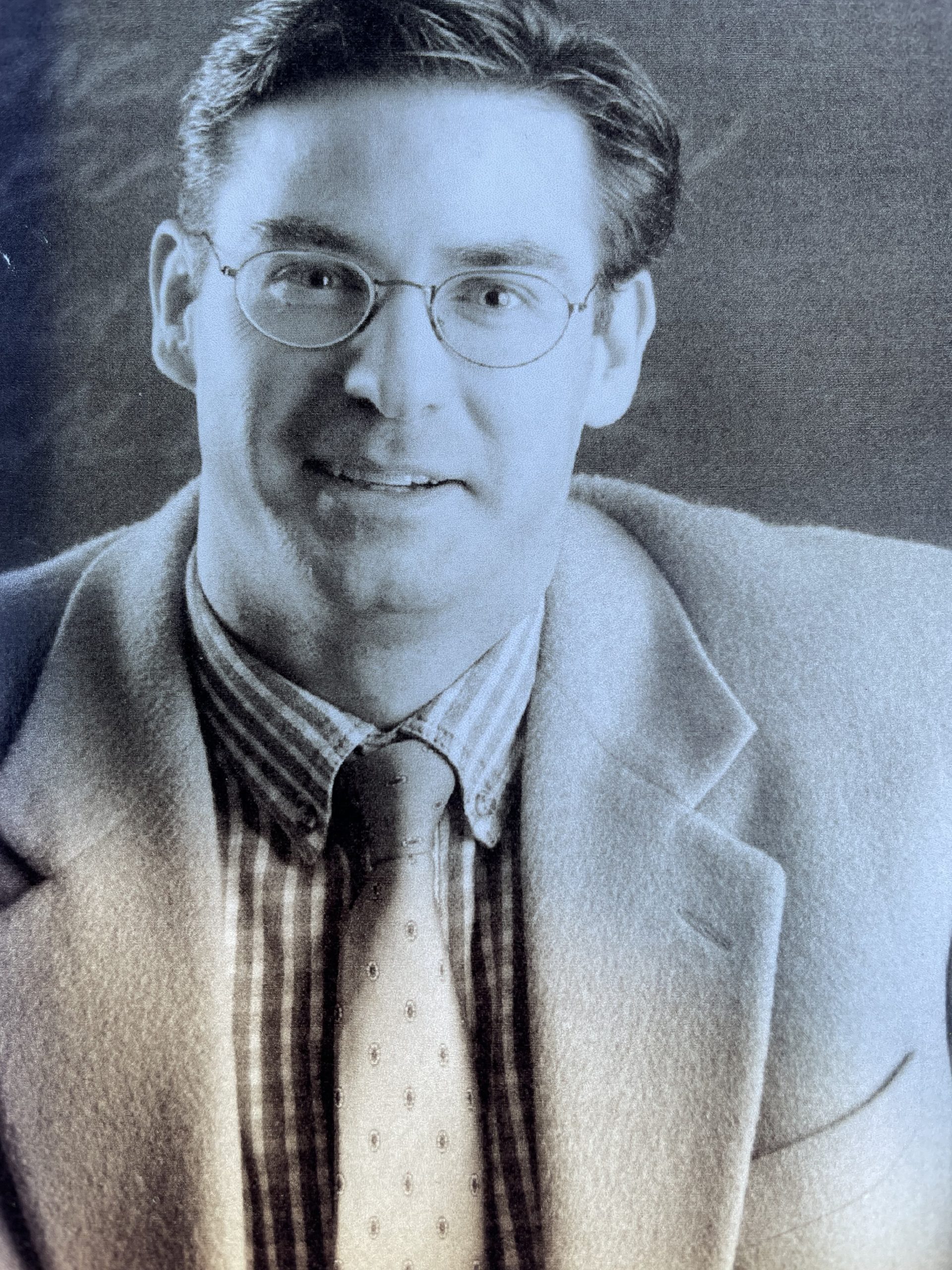

William Wik was 44.

When his body was found amid the wreckage of the collapsed building two days later, he was among several FDNY firefighters. Mr. Wik was wearing an FDNY jacket and carrying a fire department-issued flashlight.

He’d gotten out but apparently gone back in with firefighters to try to help others escape the burning building.

His brother, Thomas, who lives in Southampton, said at the time it was not surprising that his younger brother had turned back to try and help, as he had throughout his life: “He was the kind of guy who touched people — a coach, a friend, a hero,” he told The Press that week.

Mr. Wik left behind a wife and three children.

Kathleen Wik said that her family was among the lucky survivors of those who perished in the buildings. Mr. Wik’s body was removed with those of other firefighters, the heroes of the day, and given priority for processing. When it was discovered that he was not an actual firefighter, photos of identifying marks were shared with those coordinating identifications.

“He had a large rose tattooed on his arm, so it was easy to identify him,” Ms. Wik said. “He had been with the firemen, so they processed [his remains] and we were able to get his body the next week.”

Nearly 5,000 people attended William Wik’s funeral, which was held in Bronxville, where the Wiks had grown up, spending summers in Southampton.

“I feel so sorry for the people who never got them back,” Ms. Wik said of the more than 1,000 victims of the attacks whose remains were never positively identified. “We were blessed.

“Everyone in the family got the rose tattoo.”