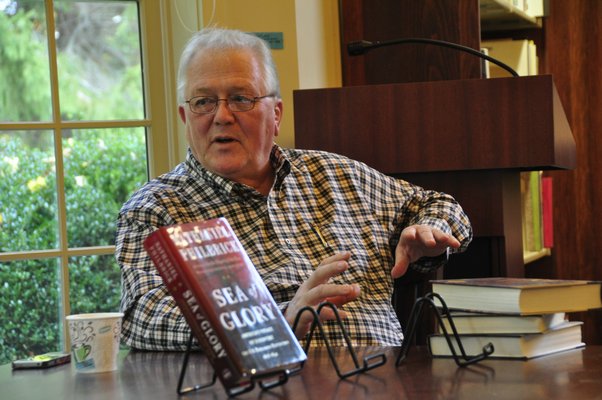

Phil Keith pulled out a chair at the end of the table last Sunday afternoon and surveyed the room in the Quogue Library. Eight pairs of eyes looked back at him. They belonged to avid readers and solemn veterans, much like himself.

He sat down and smiled warmly.

The group had gathered for a reason: to discuss writing military novels, a hot commodity in the publishing world, said Mr. Keith, who has written two wartime books, soon to be three. But perhaps there was more beneath the surface, less than 48 hours before Veterans Day, as the author launched into a story of his own.

It was the heat of SERE training—the Navy and Marine Corps Survival, Evasion, Resistance and Escape program—and he had lost track of time. He had been stuffed into a box half his size at a staged Vietnamese prisoner of war camp, locked in a tiger cage for 12 hours. A hard blow to the jaw had cracked it in two. And he knew what it felt like to nearly die, he said, as he was waterboarded by his faux captors.

“Mentally and intellectually, you know this is not real and this is a process that has an end date,” he recalled. “But when you’re in the middle of it, I promise you, it doesn’t feel like that.”

One morning, Mr. Keith and his fellow Navy men were gathered in the compound around a flagpole. The commandant, in broken English, said, “Now you Yankee dogs are going to salute my country’s flag.”

“Oh, shit,” the men muttered among themselves.

Two guards attached a flag to the pole and ran it up. It was the Stars and Stripes.

Their training was over.

“Out of all the guys who were there,” Mr. Keith said, “I can tell you, there wasn’t a dry eye in the house.”

The room was quiet as his audience nodded. It wasn’t the first Vietnam story they had heard—or, for some of the veterans, lived themselves—and it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

“What editors of the big houses like about this niche—non-fiction military or veteran books—is that it’s a very steady market. It, typically, has a good following,” he said. “But even within the niche, there are places that are stronger than others.”

Currently, World War II sits at the top of the list, as does the epic “Unbroken” by Laura Hillenbrand, who chronicles the life of Louis Zamperini, an Olympic runner taken prisoner by Japanese forces. A film based on the number-one New York Times bestseller, directed by Angelina Jolie, will release on Christmas.

“It’s one of my favorite books,” Mr. Keith said. “It’s remarkable.”

World War II is followed closely by Vietnam-era books—including “Black-Horse Riders” and “Fire Base Illingworth” by Mr. Keith, a 24-year Navy veteran with three tours in Vietnam under his belt, though his two efforts tell the stories of others, not himself.

And books set during the Civil War are never-ending, he said. There’s practically a cult following, he said, recommending “This Republic of Suffering” by Drew Gilpin Faus.

“The current, probable king of the military genre is, of course, Jeff Shaara,” Mr. Keith said, holding up a copy of “Gods and Generals.” “His dad, Michael Shaara, wrote a couple of really good books and, unfortunately, died of a heart attack. Jeff took over the family business, so to speak, and he’s turned out some tremendous books, not only on the Civil War but World War I.”

The first World War is making a strong comeback, he said, as the 100th anniversary of America’s participation in the war approaches. And, unsurprisingly, the least-read genre of military novels is that set in Iraq and Afghanistan.

“We’re tired, as a public, in general, and that’s too bad for veterans. It’ll change,” said Mr. Keith, who also writes the “Mostly Right” column for The Press. “And Korea, which they call the ‘forgotten war,’ has been in many ways—in publishing, as well. I’m sad to say that veterans from World War II, I think the latest is a thousand are passing away each day. Chronologically, the next conflict is the Korean War, and we might see a bit of a renaissance there.”

He paused, and added, “I have a great story about the Korean War that I’d love to write.”

It was December 4, 1950, and a young man named Thomas Hudner was part of a six-aircraft flight supporting U.S. Marine Corps ground troops trapped by Chinese forces. His wingman, Jesse Brown—who was the first African-American naval aviator, Mr. Keith said—was flying his F4U Corsair at a low 700 feet over the Chosin Reservoir when the plane began shuddering. The Chinese had hit him with small arms fire—they had no anti-aircraft capabilities, other than huddling in a tight circle and shooting their handheld weapons at targets overhead—and he was losing fuel.

He crash-landed into a snowy, bowl-shaped valley behind Chinese enemy lines. The engine was blown off the front of the plane. It soon caught fire. And Mr. Brown was trapped.

“His mates were circling above, and they thought he couldn’t have possibly survived,” Mr. Keith said. “But Tom flew by very slow and very low. He sees the cockpit go back and Jesse wave.”

The closest helicopter was at least 30 minutes away. The Chinese were coming over the hill. Mr. Hudner lined up his own plane with Mr. Brown’s and did the only thing he could: He plowed into the snow right next to his wingman.

It didn’t take long to conclude that Mr. Brown was severely trapped, his leg jammed underneath the controls. Mr. Hudner ran back to his plane and grabbed an ax, hacking away at the twisted metal while trying to keep his friend conscious.

A few minutes later, a helicopter arrived with a Marine pilot. They tried to free him, unsuccessfully, and found themselves left with one option: amputation.

“Tom was ready to do this, and Jesse looked up and all he could say was, ‘Tell Daisy I love her,’” Mr. Keith said. “And he was gone. Loss of blood.”

The helicopter was forced to leave at nightfall with Mr. Hudner, who had begged to extract his friend. Before they took off, he leaned over Mr. Brown and whispered in his ear, “I will be back.”

It took him 60 years. At age 89, Mr. Hudner—who received the Medal of Honor, not to mention “a chewing out from his commanding officer for ruining a perfectly good airplane,” Mr. Keith said—returned to North Korea last autumn with one mission: to retrieve Mr. Brown’s body. Without a pinpointed location, and due to bad weather, he was unsuccessful, but plans to return again.

“I’d love to write that story. I’d like to be back here in a couple years and say, ‘This is what I did,’” Mr. Keith said. “That tells you where the current market is. I started this writing game very late in life. I didn’t have my first book published until I was 60. I guess I’m the poster child for ‘it’s never too late.’ If you’re thinking about writing books, it’s never too late.”