If you define a dairy as any farm with more than eight cows, there were once 42 operational diary farms in East Hampton alone, according to the newly opened East Hampton Farm Museum. At that time, “most of the milk was for local consumption,” said Robert Hefner, historic preservation consultant for East Hampton Village.By the 1960s, most dairies on the East End had been shuttered, with the last two operating into the early 1980s—Carwytham Farm in Bridgehampton and Cow Neck Farm in North Sea.

“The land became more valuable for horses and farming,” said Prudence Carabine, a founding member of the museum, when recalling the decline of dairy farming in East Hampton in the 1950s and 1960s. “Those forces aren’t at work in other places of the country.”

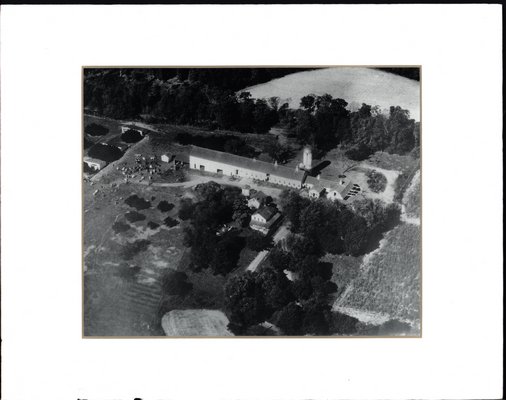

But now, many of the existing dairy barns are being torn down because, of course, they are very large and old,” Ms. Carabine said. Although fires and development have claimed most of them, there are a few dairy barns left—and the ones that remain are known by former employees or neighbors.

Claes Cassel, an East Hampton native, remembers working on Cove Hollow Farm in that village at age 12, when the farm boasted 55 cattle. As a teenager, he worked at Dune Alpin Farms, which was owned by Abe Katz, before the land was transitioned to condominiums in 1981. Mr. Cassel has worked on dairies, on and off, his entire life, and is now part of the team at Mecox Bay Dairy.

In addition to being a 365-day-a-year job with an early wake-up call of 3:30 a.m., dairy farming produces a lower gross income per acre versus other crops like vegetables. This is especially true if the dairy is producing only milk.

“A dairy farm is a low-intensity use of a high-value resource, the land,” said Art Ludlow, a local farmer whose family stopped raising cows in 1959. They doubled down on farming potatoes until 2001, when Mr. Ludlow founded Mecox Bay Dairy and reintroduced dairy farming to the East End. Their current dairy barn is a retooled potato barn.

“The thing that kept this community going for 14 generations was the farming and fishing,” said Ms. Carabine, who hails from a 12th-generation Springs farming family. “Families supported each other,” she said.

“I do feel like I am fulfilling a need. It is identifiable. It is from these cows right here, what they are eating,” Mr. Ludlow said. After researching the industry in New England, he realized that if he sold artisanal raw milk cheeses, as well as meat, he could make enough per acre to validate the operation.

During a tour of the aging room, Mr. Ludlow’s enthusiasm for the creative aspects of cheese-making was evident,as he showed the different stages of his Mecox Sunrise or cheddars on the shelf. He enjoys the variety of the work, whether that is deciding how to feed the cattle during the current drought or milking the cows on Sunday at 5 a.m., a “therapeutic” time when no one else is around.

In addition to Jersey cows—a breed he said is the “prettiest”—Mr. Ludlow raises Berkshire pigs and turkeys. A few years ago, he began to use his bull calves for meat, grass-feeding them before sending them to upstate New York for slaughter. Although the beef business is taking off, Mr. Ludlow still keeps some of his favorite milk cows around, including one of his first—Meri-Acres Beretta Maid.

Mr. Ludlow sees a burgeoning slow food movement on the East End, between his own farm and others like Amber Waves, which has reintroduced wheat to the East End, a project that Mr. Ludlow’s son Peter is participating in by growing grain. However, Mr. Ludlow is concerned that in the future the USDA might outlaw raw milk, a potential move that he describes as “political.”

“This is about food choice,” said Mr. Ludlow, who tests his milk regularly and is attentive to the health of his herd. “I can sell raw chicken; let people make their own choices.”

He continued: “One reason that we are so unhealthy with obesity is because of the increase in processed foods that are not nutritious.”

Some say the regulation of milk, through pasteurization, was part of the reason dairy died out on the East End.

“That basically lost the identity of the milk, it became a commodity,” said Mr. Ludlow, who shared a story about his mother, who grew up in Yonkers, buying milk from a farmer down the road. She would carry an aluminum container every few days to get raw, fresh milk. Later on, when milk was pasteurized and “comingled,” it lost the particular flavor from a farm. On the East End, it would be processed and mixed together at larger distributors like Schwenk’s Dairy or G&T Dairies.

“The resort nature of this place played against the farmer,” said Ms. Carabine as she recalled the problems that farmers faced in the 1960s in addition to pasteurization and increased land value. “God forbid the tractors buzz on the weekend and make dust and make noise.”

She said no one could have predicted the “stratosphere” level of real estate development that began in the 1980s. It is “one of the forces on all of us out here," she pointed out. "People will buy our land and put big houses on it, and live there six weeks of the year.”

"