Officials who hope to have a new affordable housing funding source at their disposal starting in 2023 if voters approve the Community Housing Fund in November said this week that new strategies, like large “shared equity” loans to prospective homebuyers and the purchase of small homes that are currently the region’s defect affordable housing are hopefully avenues to being able to ease the housing crisis in the region once financial resources are available.

Loans of up to $400,000 could be made under the bylaws for the Community Housing Fund, boosting a would-be buyer ability to secure a mortgage that would give them a chance to compete in the hyper-inflated South Fork housing market, the fund’s author surmised.

The new funding could also give towns the power to keep modestly sized homes in middle-income neighborhoods from being torn down and replaced with much larger dwellings that are quickly out of reach for even relative well-off local homebuyers.

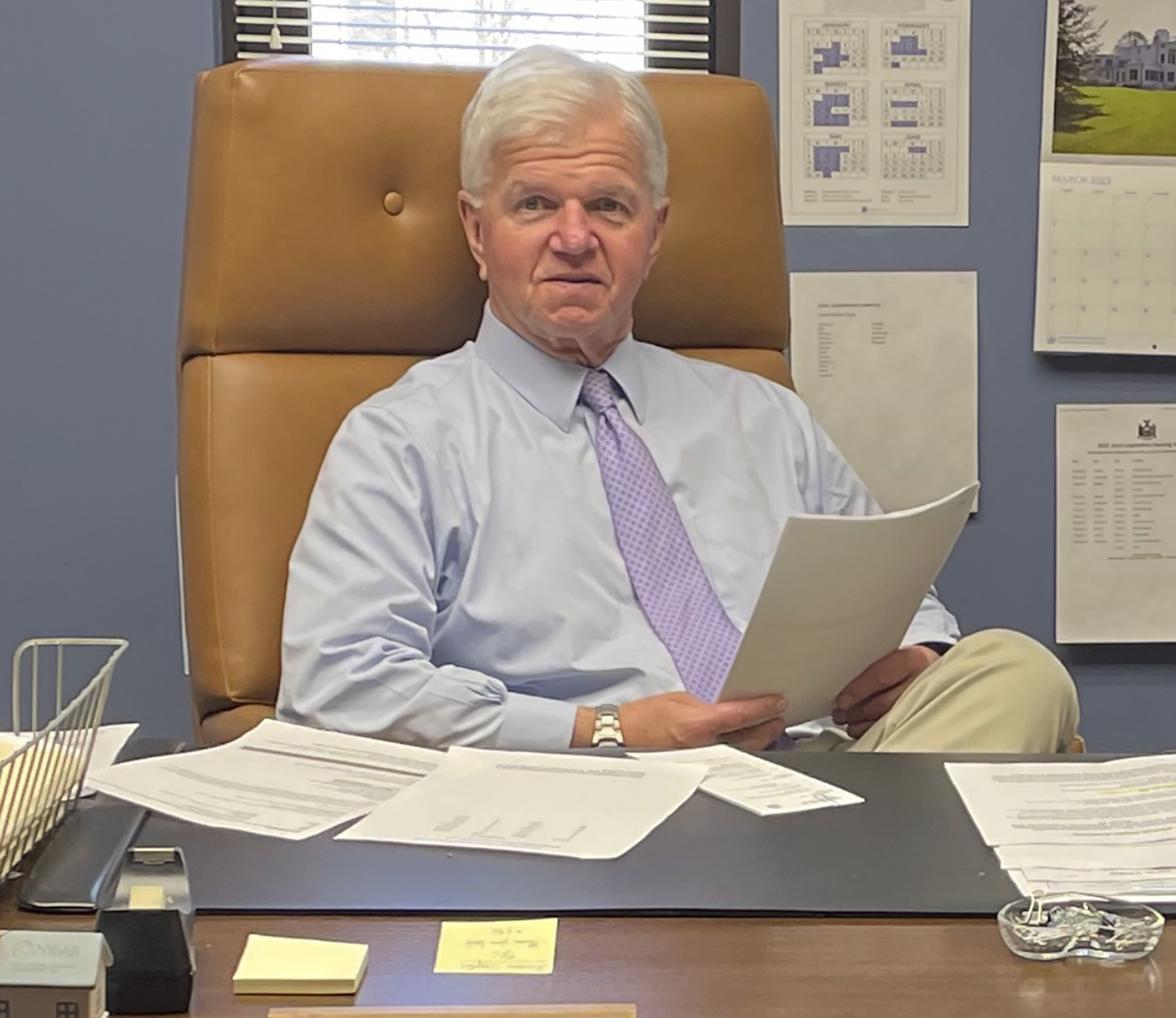

The new strategies were some of the many possible avenues for applying funding generated by the CHF that were spitballed in a panel discussion hosted by the League of Women Voters of the Hamptons, Shelter Island and North Fork on Tuesday evening on SeaTV. The forum included State Assemblyman Fred W. Thiele Jr., who crafted the legislation approved by the State Legislature last year; East Hampton Town Housing Department Director Tom Ruhle; Southampton Housing Authority Director Curtis Highsmith and Shelter Island Councilwoman Amber Brach-Williams.

The need for more affordable housing on the East End has been described repeatedly in recent years as “a crisis,” as traffic has worsened, employers struggled to find staff and local emergency services withered as more and more local residents choose to settle elsewhere where housing is more readily available at middle class prices.

“The need, we see it every day, it’s in our face,” Thiele said. “And it’s only been exacerbated by the pandemic, because the pandemic has raised prices and reduced supply. The demand and resources of those trying to buy a second home are outpacing the ability of those who need a first home to compete in the market.”

The Community Housing Fund is written to help even those earning solidly middle-class salaries, not just low income workers, Thiele said. The fund’s assistance would be available to those making well above the median income — about $150,000 per year for a family of two.

“You would be hard pressed to find a home in Southampton or East Hampton or Shelter Island for under $1 million right now,” he said. “We couldn’t use the state numbers for Suffolk County because housing prices are so much higher just on the East End.”

Four of the five East End towns will have referendums on the November ballot asking voters to approve the imposition of a new half-percent sales tax approved by the State Legislature last year specifically for the East End on real estate sales over $400,000. Riverhead Town chose not to propose creating its own fund at this point, but could still do so in the future.

If approved at the polls, the new tax would be in effect from 2023 until at least 2050. The program is modeled after the hugely successful Community Preservation Fund, which has generated over $1 billion for open space preservation and water quality improvements since it was created by referendum in 1999.

Southampton Town and East Hampton Town have already adopted the project plans, laying out how they expect to use the money generated by the fund — which is expected to be several million dollars per year in both towns — and Shelter Island will hold a public hearing on its plan in October.

Ruhle said that East Hampton hopes to direct funding toward more municipally-subsidized housing developments, in the form of rental apartments, condominiums and single-family homes.

Highsmith said Southampton Town — which lags far behind East Hampton in housing units created over the last 30 years — has plans in the pipeline for the construction of 16 single-family homes that will be sold at subsidized rates in the next three years.

Thiele said the towns can apply the funding to any projects they see fit.

“It could be the town creating housing for ownership, it could be rental housing, it could be single family housing, it could be multi-family housing, it could be accessory apartments,” Thiele said. “Anything they can possibly think of — and maybe some things the towns haven’t thought of yet.”

But municipally subsidized construction projects, no matter how ambitious — East Hampton Town is working on plans for a development of nearly 60 rental units — are always going to be modest compared to the demand, Highsmith noted.

The housing officials and the state lawmaker echoed a common refrain from the many discussions about the housing crisis in recent years: “We can’t simply build our way out of this,” Thiele said. “The demand for housing is extraordinary. We have to find ways to make existing housing more affordable.”

To that end, Ruhle said, one of East Hampton’s strategies will be to help protect what is already affordable but low-hanging fruit for profit hunting redevelopment.

“We have small homes that are nothing but tear-down targets, to be replaced with a six-bedroom house with a pool worth $2.4 million,” he said. “Hopefully, by reinvesting, we can save some of these smaller houses … and keep the character of the community, instead of just every single house maximizing the square footage that changes neighborhoods and drives up prices.”

Another tactic that Thiele, Ruhle and Highsmith also said they hope will help lift more middle-class families into the housing market is the concept of shared equity: the town lending large amounts of money to a homebuyer, with the understanding that when the house is eventually sold, the town recoups the same percentage of the ultimate equity in the house that it put in.

“The biggest problem for someone trying to buy a house is getting into the market — a down payment, or having enough to get a bank mortgage,” Thiele explained. “The Community Housing Fund could provide up to $400,000 to that person to then go and leverage that to get a bank loan.

“But it wouldn’t be a gift, it wouldn’t be a give-away,” he added. “The town would have shared equity of that house. So at the other end, when the house gets sold five years later for $1.5 million, if the town had 50 percent equity at the beginning they would get 50 percent of the equity out of it. That money would go back into the housing fund to help another family and the person that got the benefit in the first place would have their half of the equity to go buy a bigger, better house.”

Highsmith said that the prospect of funding being in place to turbo-charge the race to create housing before critical local human infrastructure like volunteer fire and ambulance departments and hospital emergency rooms run out of the manpower they need is a hopeful one. But the daily reminders of how far behind the curve they already are is daunting.

“The housing authority manages five waiting lists for different projects — each one has over 1,000 names on it,” said Highsmith, who built an accessory apartment onto his house for his son and his family to live in when they could not afford to buy a home. “That’s a problem. There’s never a week that I don’t get a phone call from someone in tears because they have to move farther west, or out of state. Something has to be done.”