David Stiles, a Hampton Waters, East Hampton resident for close to 60 years, made his name, and still practices his calling, as an architectural designer creating and building clever, whimsical tree houses — typically, two-story constructions that appeal to grownups and children who peek into rooms, grab rope ladders, haul up lunch buckets and, in general, feel like kings and queens of all they survey from upper platforms. The last time a Stiles little house was on local display, in pre-pandemic 2018 in Herrick Park, East Hampton, the kiddie queue to climb up matched the ice cream line.

Scores of how-to-build-your-own-tree house paperbacks testify to the popularity of Stiles’s concepts and designs, photographed and described by David’s wife, Jeanie, and constructed mainly with the body-and-soul assistance of R.J. (Toby) Haynes, an artist whose paintings and drawings appear often in East End galleries. The Stiles’ most recent publication, out this past June, is called “Backyard Playgrounds: Building Amazing Treehouses, Ninja Projects, Obstacle Courses, and More.” But who knew about the cartoons?

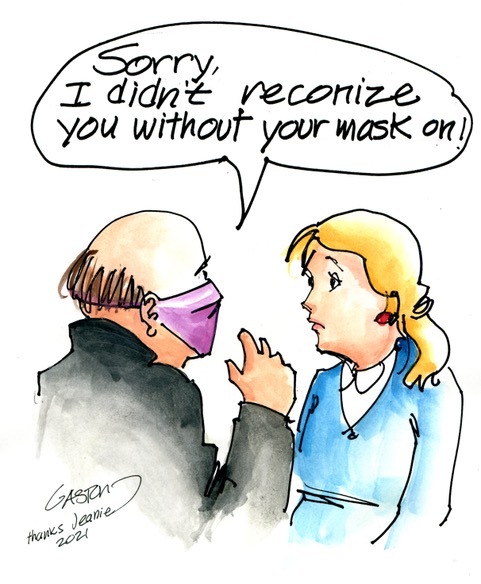

Indeed, the name “Stiles” evokes various versions of “Oh, the tree house guy.” It comes as a surprise, therefore, that many of his most devoted fans do not know that David Stiles started out as a cartoonist, and still keeps at it, producing for the last few years several a month. He describes cartooning as a “hobby,” providing him with “relaxation, freedom, fun ... I enjoy thinking up crazy ideas and sharing them with friends.” They’re also release from his professional world which “involves drafting exacting plans and measurements to scale.” And, of course, he hopes the cartoons also provide diversion in our challenging times.

Cartoons are often linked with illustration (explanation), animation (video, with sound) or comics (panels) but they have a distinct history. The word underwent major change since it first appeared in the 1600s to define the board, or chart (“cartone”) on which a sketch was done, usually a model for a larger image or sculpture. Then it moved from being medium to message, usually political, and ranging anywhere from gently humorous to satirically biting (think 18th century). For sure, cartoons were not for kids.

Cartooning was Stiles’s first love in the sixth grade, when he realized he wanted to work for Walt Disney (Ah, “Pinocchio”!), and when his father , a career captain in the U.S. Navy, drew a PT boat for him, color and all, it was for David an “Aha” moment. A stint with “Stuperman” at summer camp followed (“a skinny kid wearing a red cape and getting into trouble”), and when he attended Duke University he did cartoons for the student paper.

His heart, however, was on art and he transferred to Pratt (“my alma mater”), where he concentrated on industrial design (“just perfect for me”) and met classmate Marilyn Church, a fine arts painter famous for her courtroom sketches at high-profile trials. Both of them realized the necessity of drawing fast (“three or four minutes”). At Pratt, he fell under the influence of Calvin Albert, an abstract expressionist sculptor and painter who memorably taught him figure drawing. One sees in the cartoons the knowing line of less-is-more. He sketches in pencil and then copies them darker on a Xerox machine, figures outlined in black, “vignettes never to the edge.”) Every artist needs two artists behind him, he likes to say, “one to get started, the other to tell him when to stop.”

“Current events, especially social faults” draw his interest … and ire — none more so recently than con jobs in art, as shown in his cartoon “Invisible Art.”

“Question,” he wryly asks, “does something have to exist before it becomes invisible?” It was just this past May when “Italian conceptualist” Salvatoro Garau auctioned off his empty space “Immaterial Sculpture” for $18,300. Prior to that, Mauricio Catalan got $120,000 for “Banana with Duct Tape” at Art Basel in Milan. Stiles, who likes to turn his satiric eye on authoritarian political figures, gun-rights advocates and hustles, especially in art, says that “today is a perfect age for cartoons. People need to laugh at issues and at themselves.”

He hopes that they will look at his cartoons and “recognize something familiar in their own lives … If my cartoon can brighten their day and give them a laugh, I’m happy.”