A decade ago, Christopher Walsh found himself in a New England attic, unrolling a dozen paintings by a man he barely knew.

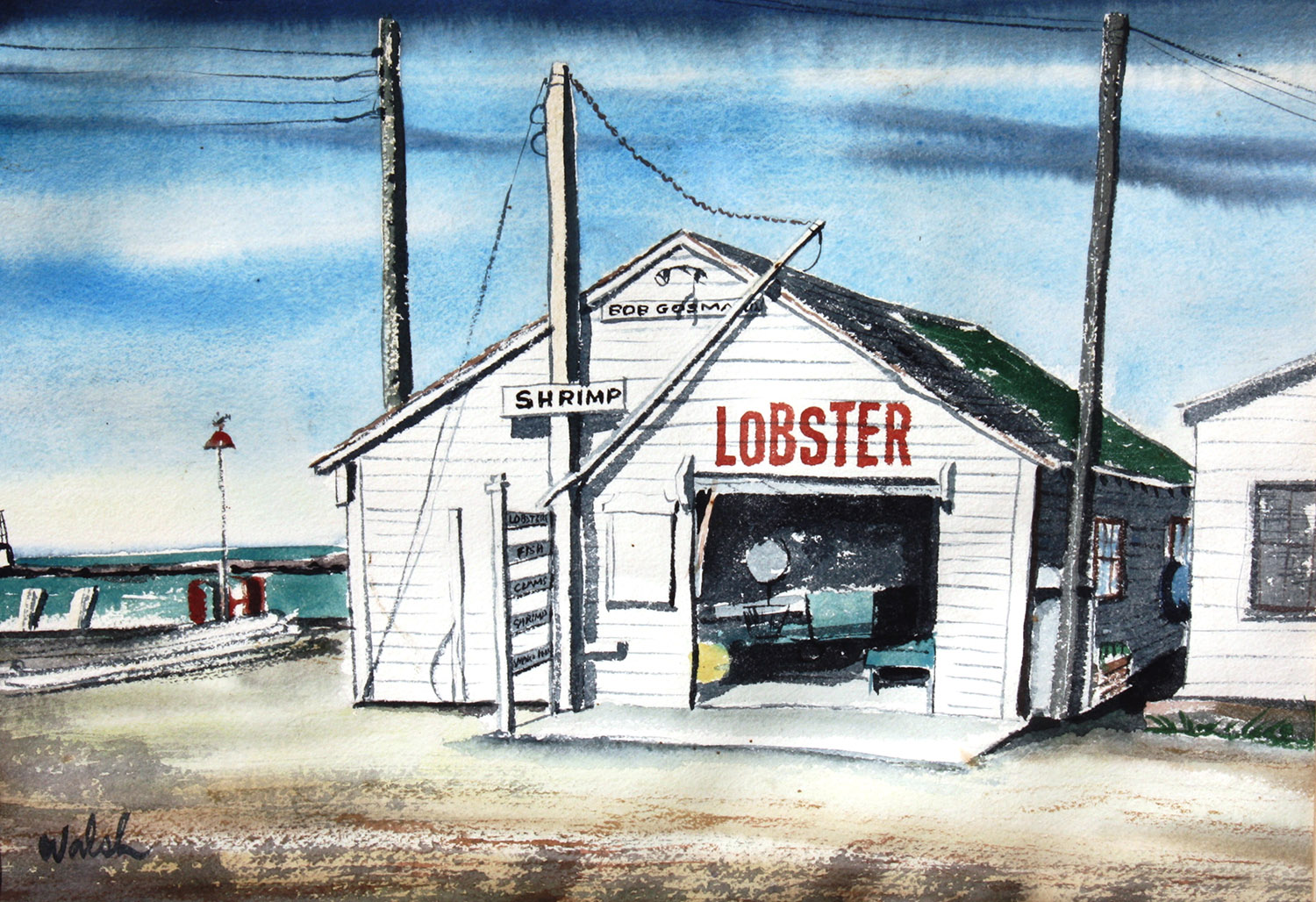

There were nautical watercolor scenes of fishermen and boats, reminiscent of his childhood summers spent in Montauk. He peered at strikingly different, modernist oils, and wondered what caused the shift.

What his father — artist Kenneth B. Walsh — had been thinking.

“There’s such a distinct change, or evolution, from the 1960s watercolor stuff, which depicts a lot of local scenery, to the 1970s abstract stuff,” Christopher Walsh said. “It almost seems like a different person has painted it.”

Today, this art serves as his only clue, and Walsh is determined to find as much as he can. A years-long search for his father’s lost paintings has recently accelerated, leading him up and down the East Coast, and beyond, to bring the collection together — a selection currently on view at East Hampton Town Hall.

“I’m not an art critic. I’m not a student of art, so I don’t know where this all fits in,” Walsh said. “That’s for the world to decide. Just to be known, and to be respected for what he did, is my goal.”

Now a reporter for The East Hampton Star, Walsh first wrote a letter to the local newspaper in February 2012, soliciting help to locate his father’s paintings. To his surprise, the response was immediate and swift, and he quickly found two paintings at the Montauk School, and one at Gosman’s Dock.

His pursuit has extended far beyond the East End, from Westchester and Nashville to cities farther south in Georgia and Florida, where he reunited with relatives and finally became acquainted with those who know his father better, or at least longer, than he did.

“Through speaking with family members, who are older than me and knew him longer than I did, I did get a more complete picture of this evolution of him as an artist, and just came to know him better, as well,” Walsh said of his father. “This thing has snowballed, but in slow motion. I’ve learned about a bunch of work that I didn’t know existed, and actually acquired them, as well — which is really, really fulfilling.”

[caption id="attachment_88248" align="alignright" width="503"] "Untitled" by Ken Walsh.[/caption]

"Untitled" by Ken Walsh.[/caption]

One of nine children, Kenneth B. Walsh grew up in Depression-era Boston, hunting and fishing in the Fells to help his ailing father provide for a large and growing family. In his early 20s, he served as the co-pilot of a B-17 “Flying Fortress” during the last years of World War II in Europe.

“As I became a young adult, when I was 22 or so, it dawned on me that, wow, he was in Europe co-piloting a plane getting shot at by the Germans, at the age that I am now,” Walsh said, “which gave me a lot of respect for him. Once you’ve done that, it’s hard to imagine anything scaring you anymore.”

In the early 1960s, Kenneth Walsh — now the successful businessman behind Bonart Studio in New York — built a house in Montauk and began to depict the area’s natural beauty in watercolor paintings, exhibiting and selling them at the Bonart Gallery at Gosman’s Dock. Over time, he delegated more of his commercial art studio’s work to employees, spending time at home in Hither Hills with his family.

Their walls were filled with his watercolor and acrylic paintings, and collages from driftwood he found while beachcombing. He loved to sing and fish and drive his Jeep along the dunes. He could create something out of anything, his son said.

“We used to have these wonderful parties on the beach on summer nights,” he said. “We’d drive way down to Shagwong Point in Montauk with a whole bunch of food, and the kids would run around and play and swim, and the adults would drink a lot of wine and cook. It was great. It was just great. You could not ask for a happier childhood.”

It was not to last, Walsh said. In 1971, the artist’s bipolar disorder manifested and destroyed his business, and the family of seven moved full-time to Montauk. He slept most of the time, weighed down by heavy medication, but finally began to paint again when his depression lifted a few years later.

“That was when the new style emerged, and he was painting one right after the other for a few years, in the modernist style,” his son recalled. “My mom said he could be so driven that he would work for 16 to 18 hours at a stretch.”

By 1980, his illness had reared its ugly head once again, as did bone cancer, and Kenneth Walsh died at age 58 on September 5, 1980, in a Veteran’s Administration hospital in Brockton, Massachusetts, just 30 miles from where he was born.

It was two days before Christopher Walsh turned 14. Shortly after, the family relocated to Massachusetts, to be near relatives.

“That was really rough. He wasted away, died within a year of getting cancer,” Walsh said. “That happened just as I’m in the throes of adolescence, so that sucked, and I was in a new town and a new state, at a new school. Then, three months later, John Lennon was shot and killed. I had met John and Yoko Ono when I was 9 in Montauk, and that was the biggest thrill of my life because I’m so into music. So to have that happen so soon after, it was kind of numbing, I suppose.”

With more than 50 collected works, Walsh has found a portal through which to reconnect to his father. His art is a lifeline to a man he wishes to know. An artist whom, he hopes, will be widely respected someday — “nothing more,” he said of his vision.

“He wasn’t perfect. He was complicated, as most of us are,” he said. “But in my biased view, he put out a really impressive body of work, so it’s been really important to me to try to make sure that stuff stays in the family to a degree, but also gets out in the world as well.

“I don’t have a specific goal in mind, but I’m hoping that by doing this, good things will happen,” he said. “And so far, it’s been all good.”

Works by Kenneth B. Walsh are currently on view at East Hampton Town Hall, located at 159 Pantigo Road in East Hampton. For more information, visit kennethbwalshart.com.